A música wagneriana é absolutamente divina, grandiosa, eloquente e mística. Poderá ser bem ou mal interpretada, melhor ou pior encenada...

Bayreuth 2008 tem revelado uma interessante particularidade: a controvérsia não se centra na prestação dos intérpretes, mas antes nas encenações! E por que não ?!

Embora a edição corrente do festival de A Colina Verde conte ainda com escassos dias, são as propostas cénicas da ambiciosa e incompetente Katharina Wagner (Os Mestres Cantores de Nuremberga) e do agraciado Herheim (Parsifal) que têm feito notícia.

À semelhança da edição passada - vide aqui e aqui - , a encenação de Katarina foi apupada, sem clemência. Já a nova produção de Parsifal é alvo de constantes elogios.

A respeito do Parsifal de Harheim, eis o que nos diz o The New York Times:

«The production is about change, as a matter of fact. Stefan Herheim, the 38-year-old Norwegian director, liberates this Christian saga about purification from its nasty associations with anti-Semitism and remakes it into a metaphor for modern Germany. This is not in itself a new tack for a country that for decades has been wrestling on opera stages with its history, but simultaneously Mr. Herheim has reconceived “Parsifal” as an allegory for Bayreuth itself.

The opera unfolds at Wahnfried, Wagner’s home there, with the prompter’s box turned into the composer’s grave and site of the Holy Grail. A bed, placed center stage, where Parsifal’s mother dies and Kundry fails to seduce our boyish hero, is the locus of more comings and goings than a bedroom in a French farce, and it’s the obvious symbol of birth and death. Gone are the long Wagnerian stretches of inaction. Sets and singers are in constant motion.

Scenes of Wilhelminian Germany vanish before filmed backdrops of World War I, then yield to orgies of Weimar decadence, with Flower Maidens cast as copulating showgirls, nursing convalescing troops of Grail knights. The evil Klingsor wears fishnet stockings and high heels; Parsifal, a child’s sailor suit. You have to admire the singers’ sang-froid.

Most startling was to hear straight-faced, seasoned Bayreuth fans during intermission express surprise at the sight of Wehrmacht soldiers and Nazi banners during Act II, recalling old days at the festival. It all seemed so inevitable. Postwar ruin, gorgeously imagined, then morphs in the finale into the Bundestag in Bonn, with torpid knights as politicians, and Wagner’s death mask, projected, floating in a ghostly ether.

By this point, it’s hardly worth troubling yourself to parse how, precisely, Parsifal — having gone on his quest of sacrifice and knowledge, to return weathered and wise and save the day — serves the metaphor of a newly reunited German democracy and a refreshed Bayreuth. Redemption, suffice it to say, rewards those who, having squandered glory to false idols, face squarely the past. A large mirror turns toward the audience, implying our own obligations to history. Or some such.

Mr. Herheim’s production, with dreamlike sets by Heike Scheele, arrives after a pilloried “Parsifal” by the provocateur Christoph Schlingensief, and after many years before that of modernist performances that skirted the opera’s less tasteful narratives. The new version clearly signals deliverance from all that, its solipsism well suited to Bayreuth’s insular culture.

In the end, it is moving. Directors get away with half-baked ingenuities because opera plots already require suspended judgment — and because of the music.»

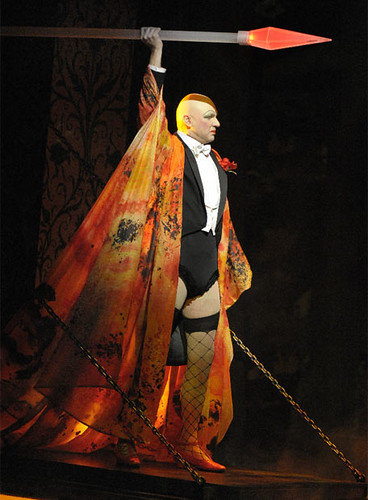

(cena de Parsifal, Bayreuth 2008)

Quanto ao logro de Os Mestres Cantores de Nuremberga, o El Pais resume do seguinte modo a proposta de Katharina Wagner:

«El trabajo de la última de los Wagner está salpicado de hallazgos, pero no tiene continuidad y su narrativa es confusa. Luego está el peso de la historia. Los maestros cantores era la ópera preferida de Hitler, por su reivindicación de un nacionalismo alemán.

Ello influye en la directora que se plantea un ajuste de cuentas no sólo con los valores tradicionales e idealizados del pueblo alemán, sino que pone en tela de juicio el arte sagrado alemán, ridiculizando -con gracia- a celebridades de la cultura, desde Goethe, Schiller, Durero, Bach, Beethoven o Lessing hasta el mismísimo Wagner. En el proceso de poner todo patas arriba hay una inversión de valores - sustentado en la propia música según Katharina- de los personajes principales, de tal manera que los modélicos Sachs y Walter no superan éticamente al en otras ocasiones mezquino Beckmesser.

Todo este conglomerado hay que llevarlo adelante con mucho rigor para ser creíble y Katharina, bien por la presión, bien por su falta de experiencia tiene momentos de ingenuidad y hasta torpeza que afectan sustancialmente al conjunto. Todo ello sin negar su audacia y su inventiva.»

Bayreuth 2008 tem revelado uma interessante particularidade: a controvérsia não se centra na prestação dos intérpretes, mas antes nas encenações! E por que não ?!

Embora a edição corrente do festival de A Colina Verde conte ainda com escassos dias, são as propostas cénicas da ambiciosa e incompetente Katharina Wagner (Os Mestres Cantores de Nuremberga) e do agraciado Herheim (Parsifal) que têm feito notícia.

À semelhança da edição passada - vide aqui e aqui - , a encenação de Katarina foi apupada, sem clemência. Já a nova produção de Parsifal é alvo de constantes elogios.

A respeito do Parsifal de Harheim, eis o que nos diz o The New York Times:

«The production is about change, as a matter of fact. Stefan Herheim, the 38-year-old Norwegian director, liberates this Christian saga about purification from its nasty associations with anti-Semitism and remakes it into a metaphor for modern Germany. This is not in itself a new tack for a country that for decades has been wrestling on opera stages with its history, but simultaneously Mr. Herheim has reconceived “Parsifal” as an allegory for Bayreuth itself.

The opera unfolds at Wahnfried, Wagner’s home there, with the prompter’s box turned into the composer’s grave and site of the Holy Grail. A bed, placed center stage, where Parsifal’s mother dies and Kundry fails to seduce our boyish hero, is the locus of more comings and goings than a bedroom in a French farce, and it’s the obvious symbol of birth and death. Gone are the long Wagnerian stretches of inaction. Sets and singers are in constant motion.

Scenes of Wilhelminian Germany vanish before filmed backdrops of World War I, then yield to orgies of Weimar decadence, with Flower Maidens cast as copulating showgirls, nursing convalescing troops of Grail knights. The evil Klingsor wears fishnet stockings and high heels; Parsifal, a child’s sailor suit. You have to admire the singers’ sang-froid.

Most startling was to hear straight-faced, seasoned Bayreuth fans during intermission express surprise at the sight of Wehrmacht soldiers and Nazi banners during Act II, recalling old days at the festival. It all seemed so inevitable. Postwar ruin, gorgeously imagined, then morphs in the finale into the Bundestag in Bonn, with torpid knights as politicians, and Wagner’s death mask, projected, floating in a ghostly ether.

By this point, it’s hardly worth troubling yourself to parse how, precisely, Parsifal — having gone on his quest of sacrifice and knowledge, to return weathered and wise and save the day — serves the metaphor of a newly reunited German democracy and a refreshed Bayreuth. Redemption, suffice it to say, rewards those who, having squandered glory to false idols, face squarely the past. A large mirror turns toward the audience, implying our own obligations to history. Or some such.

Mr. Herheim’s production, with dreamlike sets by Heike Scheele, arrives after a pilloried “Parsifal” by the provocateur Christoph Schlingensief, and after many years before that of modernist performances that skirted the opera’s less tasteful narratives. The new version clearly signals deliverance from all that, its solipsism well suited to Bayreuth’s insular culture.

In the end, it is moving. Directors get away with half-baked ingenuities because opera plots already require suspended judgment — and because of the music.»

(cena de Parsifal, Bayreuth 2008)

Quanto ao logro de Os Mestres Cantores de Nuremberga, o El Pais resume do seguinte modo a proposta de Katharina Wagner:

«El trabajo de la última de los Wagner está salpicado de hallazgos, pero no tiene continuidad y su narrativa es confusa. Luego está el peso de la historia. Los maestros cantores era la ópera preferida de Hitler, por su reivindicación de un nacionalismo alemán.

Ello influye en la directora que se plantea un ajuste de cuentas no sólo con los valores tradicionales e idealizados del pueblo alemán, sino que pone en tela de juicio el arte sagrado alemán, ridiculizando -con gracia- a celebridades de la cultura, desde Goethe, Schiller, Durero, Bach, Beethoven o Lessing hasta el mismísimo Wagner. En el proceso de poner todo patas arriba hay una inversión de valores - sustentado en la propia música según Katharina- de los personajes principales, de tal manera que los modélicos Sachs y Walter no superan éticamente al en otras ocasiones mezquino Beckmesser.

Todo este conglomerado hay que llevarlo adelante con mucho rigor para ser creíble y Katharina, bien por la presión, bien por su falta de experiencia tiene momentos de ingenuidad y hasta torpeza que afectan sustancialmente al conjunto. Todo ello sin negar su audacia y su inventiva.»