Ópera, ópera, ópera, ópera, cinema, música, delírios psicanalíticos, crítica, literatura, revistas de imprensa, Paris, New-York, Florença, sapatos, GIORGIO ARMANI, possidonices...

quinta-feira, 26 de fevereiro de 2009

quarta-feira, 25 de fevereiro de 2009

Der Fliegende Holländer, Covent Garden

Sem surpresa, a interpretação de Terfel (ossia O Colosso), como Holländer, marca a nova produção de Der fliegende Holländer (Wagner), recentemente estreada em Covent Garden.

Há uma década atrás, este superlativo registo (tal como este) levantavam a ponta do véu, fazendo crescer água na boca, tanto dos wagnerianos – como eu! -, como dos terfelianos – como eu!!

Depois disto, digam que "já não há vozes wagnerianas" – Terfel, Stemme, Meier, Heppner, Salminen, e muitos outros, chegavam para montar um Der Ring memorável, ou não?

For the moment, aqui fica a revista de imprensa deste acontecimento, marcado pela unanimidade: Terfel é sinonimo de excelência!

Pela minha parte, sei-o desde 1998, ano em que a peste operática se entranhou em mim, atingindo-se o point of no return!

«Add to that the flying Welshman, Bryn Terfel, weighing anchor in a performance of thrilling intensity more than matched on this occasion by a soprano, Anja Kampe, who simply knows no fear; throw in the Royal Opera Chorus on blistering form and a stage director, Tim Albery, for whom less is always more, and you have one of those rare evenings in the opera house that has you sitting so far forward in your seat that every muscle in your body is aching by close of play.

(…)

Enter now the flying Terfel toting a rope like it’s his lifeline or his cross to bear for all eternity. His still, dark, bulky, threatening presence is already not quite of this world and as he quietly utters the words “Die Frist ist um” (“The time is up”) you sense the weariness of his eternal torment. Terfel’s German has always been exemplary but here he uses words like a fist of defiance against “eternal annihilation”, spitting out consonants with impunity and making phrases like “barbarous son of the sea” as ugly and they are vivid. He is as good here as I’ve heard him in a long time, capitalising now on his well-marinated vocal timbre, weathered and craggy but still capable of great tenderness in those ascents into honeyed head voice.»

«Tim Albery's staging is built around Bryn Terfel's haunted portrayal of the Dutchman, and the bass-baritone unquestionably delivers. His performance is mesmerising - hauntingly well-sung, and he dominates the stage even when doing nothing at all. Set alongside the equally world-class Senta (sung by Anja Kampe, in her Royal Opera debut), Terfel secures and intensifies the core of the drama, and its climax.

(…)

But with Torsten Kerl as a sturdy Erik, Hans-Peter König a suitably stolid Daland, and John Tessier a crisp, fresh-toned Steersman, the supporting cast are first-rate. Terfel and Kampe, though, are exceptional.»

«Dragging the dead weight of the rope of destiny behind him, Bryn Terfel's Flying Dutchman appears a haunted and weary man, who seems to know from the start that his bid to break the curse that binds him to sail the seas for eternity will fail. He starts his great monologue Die Frist ist um, The Time is up, in a chilling sotto voce, which builds to a magnificent outpouring of rage, fear, despair and a thread of hope.

In fabulously good voice, carving a majestic legato line, Terfel goes on to give a performance of the grandest Wagnerian stature and, if nothing quite matches the impact he makes in this opening scene, the fault is Wagner's, not his. The remainder of the opera is dominated by Anja Kampe's equally powerful Senta. A few dud top notes and lapses in intonation aside, she sings this killingly difficult role with thrilling abandon and intensity, etching a sharp characterisation of a neurotic obsessive on a psychologically suicidal course.

(…)

Terfel and Kampe inevitably overshadow the other soloists, but Hans-Peter König's makes something of the bluff, venal Daland, Torsten Kerl sings cleanly as Erik, and John Tessier is a spritely steersman.

(…)

The orchestra plays quite gloriously throughout. But it's Terfel and Kampe who make this production quite unmissable. Book any remaining tickets now.»

(Bryn Terfel)

terça-feira, 24 de fevereiro de 2009

Disse-me um passarinho...

... que, para breve, a NAXOS (re)editará o célebre Simon Boccanegra, com o triângulo mágico: Gobbi, Christoff e De Los Angeles.

A não perder!

domingo, 22 de fevereiro de 2009

Bunuel em SALDOS!

A escassos €46,95, no sítio do costume, sem legendas em português (alternativas: inglês e francês), so what?

Há horas felizes.

Nilsson & Domingo

(Birgit Nilsson e Plácido Domingo)

Nilsson e Domingo nunca actuaram juntos, lamentavelmente.

Antes de partir, a maior das suecas líricas criou um prémio, destinado a distinguir artistas líricos extraordinários. Ainda antes de partir, a diva decidiu quem seria o primeiro galardoado: Domingo.

«The tenor Plácido Domingo, below, has been named the winner of the first Birgit Nilsson Prize for outstanding achievement in classical music, the Birgit Nilsson Foundation said on Friday. The recipient also receives $1 million. The foundation, established by Ms. Nilsson, the Swedish soprano who died in 2005, plans to award the prize every two to three years; subsequent winners will be nominated by a jury and selected by the foundation’s board, though Mr. Domingo was chosen by Ms. Nilsson before her death. In a statement, Mr. Domingo expressed his gratitude, adding: “My greatest regret was that Birgit and I never performed together in ‘Die Walküre’ or ‘Tristan und Isolde.’ I remember telling her this many years ago, to which she replied, ‘Well then, you better hurry up.’ “»

A escolha não podia ser melhor!

sexta-feira, 20 de fevereiro de 2009

Il Trovatore - Met Opera House - II - A première

«Actually, “double curse” was the way Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, referred to the company’s seeming inability to present a decent production of Verdi’s “Trovatore” in its laughably inept last two tries, in 1987 and 2000. But on Monday night the Met introduced a new staging by the Scottish director David McVicar, in his company debut. And with this “Trovatore” the Met knew what it was getting: the production was introduced at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2006.

No matter. It is new to the Met, and it works. This may not be the most imaginative or visually striking “Trovatore.” But it is a clear-headed, psychologically insightful and fluid staging.

(...)

Rather than encumbering the opera with a heavy-handed concept, Mr. McVicar simply updates the story from Spain in 1409 to the early 19th century, during the Spanish War of Independence, which makes the factional strife seem more contemporary. He and his creative team — including the set designer Charles Edwards and the costume designer Brigitte Reiffenstuel, also making their Met debuts — draw inspiration from “The Disasters of War,” Goya’s series of etchings. And the Goya imagery gives the production a consistent and harrowing look.

A tall, looming unit set rotates slowly to conjure different scenes: the gray wall of a castle, crossed diagonally by an ominous set of stairs; the secluded courtyard of a cloister; rocky cliffs to evoke both a Gypsy encampment and a dungeon where Manrico and Azucena await their deaths. In the background we see the charred bodies of victims still bound to stakes.

(...)

Though there are no real dances in “Il Trovatore,” the production team includes the choreographer Leah Hausman, in her Met debut, and she surely helped bring physical intricacy to the crowd scenes.»

Se em matéria de encenação a coisa não correu mal - a última e antepenúltima encenações que passaram pelo Met não deixam boas recordações... -, já em termos artísticos não parece ter-se ultrapassado o bom (com letra minúscula):

«Vocally, it is probably easier for the Met to cast any Puccini or even most Wagner operas than “Il Trovatore.” The roles demand everything: Italianate sound and outbursts of power, elegant lyricism and incisive attack, coloratura agility and soaring line.

Mr. Álvarez, an honorable Manrico, has a real tenor voice, full of throbbing warmth and ping. If his singing is sometimes gruff, it goes with his impetuous conception of the character. The showpiece tenor aria “Di quella pira,” which the incensed Manrico dispatches before rushing off to rescue the captive Azucena, traditionally ends with a defiant high C that while not in Verdi’s score, is something opera buffs have come to expect. The aria was transposed down a half-step for Mr. Álvarez, who capped it with a defiant high B.

Mr. Hvorostovsky may not be a classic Verdi baritone, but this distinctive artist once again makes a Verdi role his own, singing with an alluring combination of dusky colors, creamy legato and robust top notes.

(Hvorostovsky ossia Conte di Luna)

Ms. Radvanovsky won an ardent ovation for her Leonora, but her singing may divide Verdi buffs. She gives an intensely expressive and musically honest performance, letting phrases fly with bright, soaring sound and shaping passages with pianissimo tenderness. From her first appearance this vulnerable Leonora looks like a restless young woman full of yearning for her adored Manrico. Still, her sound has a hard-edged quality that is either earthy and emotional or grainy and pinched, depending on your take. I lean slightly toward the grainy.

Ms. Zajick, a force of nature, sings Azucena with demonic ferocity, a woman obsessed. Yet just as there is intelligence in her singing, there is willfulness in her portrayal. She sees Manrico both as the son she has raised as her own and as a tool of vengeance.

(Zajick como Azucena)

The conductor Gianandrea Noseda drew out dark textures and grave solemnity from the music. But he conducted many passages of steady accompaniment patterns with an expressive flexibility that at times threw the singers off and caused uneven entrances in the orchestra.»

(Il Trovatore, Met Opera House, Fevereiro de 2009)

Il Trovatore - Met Opera House - I - Antevisão da (relativamente) nova produção (McVicar)

«A GYPSY burned as a witch, infants switched at birth, mortal enemies who have no idea they are brothers: it sometimes seems that Verdi’s romantic melodrama “Il Trovatore” exists just to be made fun of. The tradition goes back a long way.

Julian Budden’s three-volume study of Verdi’s operas notes that within months of the “Trovatore” premiere in 1853, parodies were springing up not only in Italy but also abroad. That vogue for satire was “a sure sign of overwhelming popularity,” Mr. Budden wrote, adding that “of all his output, ‘Il Trovatore’ was the most loved in Verdi’s own day.” In the English-speaking world sendups like “The Pirates of Penzance” (1879) and “A Night at the Opera” (1935) are classics in their own right.

The Scottish director David McVicar, a huge star at the Royal Opera in London and elsewhere, is not among the work’s defenders. His new production, his Metropolitan Opera debut, opens on Monday.

“On a bad day I think ‘Il Trovatore’ is one of the stupidest operas ever written,” Mr. McVicar said shortly after arriving in New York. “Before I took it on, I thought that. But that’s why I took it on. Obviously it doesn’t work on an intellectual level the way Mozart’s great operas do. But at an emotive level the grand passions have huge power.”

Opera stages, notably in Germany, are overrun with university-trained director-theorists who fancy themselves whistle blowers, impelled to expose the rottenness at the core of the societies that produced them. Too often their imposed concepts and radical critiques make better polemics than theater. At first glance Mr. McVicar, 42, may seem to be one of them.

But no. His reservations about “Il Trovatore” notwithstanding, he acts as Verdi’s advocate almost in spite of himself. Maintaining the Spanish locale, he moves the action from 1409 (an unremarkable year in an era of obscure power struggles) to the still-remembered Spanish War of Independence, fought against Napoleon and memorialized for the ages in the nightmare imagery of Goya’s “Desastres de la Guerra.”

“What guides me,” Mr. McVicar said, “is that that period must work musically. The early 19th century fits with Verdi’s tinta, the dark palette he creates for Spain.”

In Mr. McVicar’s hands, “Il Trovatore” thus has a chance to emerge as the drama Verdi intended rather than as the succession of magnificent melodies less exacting interpreters settle for.

“Verdi believed in ‘Il Trovatore,’ ” Mr. McVicar said. “I don’t want to mock it. I wanted to see if I could make it work on its own terms, as I imagine he wanted it to be. All I have to work with is my imagination and my research. And the cast. I’m not a prescriptive director. I have to make the singers look closely at motivation, to find a reality that works for them. Without that the opera won’t yield up much.”

Manrico, the troubadour of the title, is both a poet and a man of war, given to fits of violence. The tenor Marcelo Álvarez has a volatile quality Mr. McVicar considers perfect for the part.

The baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky is Count di Luna, the elder brother Manrico does not know he has. In one of the trickiest moments for the stage director, the two men prowl a palace garden, and Leonora, the woman they both desire, mistakes the hated di Luna for her beloved Manrico.

“It’s dark,” Mr. McVicar said. “She’s working on smell, on the way her skin feels as the man gets close. It’s a moment we might find in Shakespeare, only he would have written it better. All Leonora’s senses tell her this is her man. And here’s Hvorostovsky with his beautiful mane of silver hair, looking nothing like Álvarez. There has to be some way to make that hair work theatrically.”

Leonora is portrayed by the soprano Sondra Radvanovsky. Too often, Mr. McVicar finds, the character comes onstage as a “poncy lady in a big frock.” To him she is closer to a Brontë heroine on the moors, or to Beethoven’s Leonore in “Fidelio,” who, like this Leonora, will stop at nothing to free her man from prison.

Neither brother, in Mr. McVicar’s view, loves Leonora for the “brave, complex, human being she is.”

“For them,” he said, “she’s more like a football. It’s almost as if they sensed their lost bond, and that’s the source of their hatred.” Despite that hatred, Mr. McVicar pointed out, neither brother proves capable of killing the other by his own hand.

At the opera’s climax Leonora offers di Luna sex for Manrico’s freedom and instantly swallows slow poison. Even so, Mr. McVicar is convinced that she fulfills her part of the bargain.

“There’s no doubt in my mind,” he said. “And for the artist it’s a far more dramatic choice. But that’s Sondra too. We’ve butched her up, made her proactive. This isn’t a lady who needs much rescuing.”

By consensus, originating with Verdi himself, the most fascinating character in the opera is Azucena, daughter of the Gypsy burned as a witch. At the same time her back story is the crux of the “Trovatore” problem. Azucena is the one who kidnapped di Luna’s brother, intending to throw him into the fire. In her confusion she incinerated her own son instead, then raised Manrico as the instrument of her revenge.

The mezzo-soprano Dolora Zajick, returning to the Met 20 years after her house debut in the part, has given Azucena’s role as the opera’s prime mover a lot of thought.

(...)

“It’s not an opera I’d choose to go and see,” he said. “Mind you, there are many Wagner operas I wouldn’t buy a ticket for. But I’m doing ‘Parsifal’ and ‘Meistersinger’ because I have to wrestle with their unsavory, unhealthy aspects. I can’t stay with Mozart in my comfort zone all the time.”»

(ensaio de Il Trovatore, Met, com Hvorostovsky em primeiro plano)

Devo adiantar o meu total acordo com a absoluta patetice do argumento de O Trovador, sem rodeios. Além da falta de consistência - ficcional, fantasiosa, no limite – da trama da ópera, o disparate atinge níveis circenses.

Paradoxalmente, esta ópera – um dos vértices da famosa trilogia verdiana, do período inicial (Rigoletto, La Traviata e Il Trovatore) – reúne das mais belas páginas da escrita lírica – verdiana e não só! -, contendo armadilhas e exigência técnicas que apenas um curto leque de artistas pode enfrentar. A famosa tirada de Toscanini – A ópera convoca os quatro maiores cantores do mundo -, entretanto banalizada, mantém toda a actualidade, tendo a sua óbvia razão de ser.

Quanto ao olhar sobranceiro de McVicar, que remata o artigo (bold da minha autoria), confesso não o entender...

Prosaicamente, parece cuspir no prato em que come, não?!

Que me perdoem a expressão, grosseira mas verdadeira, caramba!

segunda-feira, 16 de fevereiro de 2009

Inveja...

Tanto os habitantes de Estrasburgo, como os parisienses regozijam com a prestação de Nina Stemme ossia La Wagneriana!

«C'est une femme majestueuse qui s'avance sur la scène, dans une longue robe blanche fluide. Belle et sobre, avec cet émouvant petit air de Romy Schneider. Et ce calme apparent, résultat d'une carrière sagement menée : Nina Stemme a 40 ans, en 2003, lorsqu'elle révèle au grand public une Isolde qui fera doublement date, puisque c'est aussi la première fois qu'une oeuvre de Wagner est programmée au Festival de Glyndebourne, dans le Sussex (Angleterre). Un coup de maître, dont s'enorgueillit le directeur de l'Opéra du Rhin, Nicholas Snowman, alors patron de Glyndebourne : "Je l'avais entendue en 2002 à Salzbourg dans Le Roi Candaule, de Zemlinski, raconte-t-il. J'étais allé la voir dans sa loge pour lui dire : "Vous êtes mon Isolde." Elle m'avait rétorqué : "Vous avez une jolie cravate." Il m'a fallu plus de six mois pour la convaincre."

Adoubée dans la caste des grands chanteurs wagnériens (en témoigne le DVD de Tristan paru chez EMI), cette mozartienne (elle a débuté avec le Chérubin des Noces de Figaro en 1989 à Cortona) passée par un cursus en sciences économiques à l'université de Stockholm a remporté le concours Operalia de Placido Domingo. La suite est la route pavée des scènes internationales : Puccini (Madame Butterfly, Tosca), Verdi (Aïda), Berg (Wozzeck), Chostakovitch (Lady Macbeth, de Mzensk), Strauss (Le Chevalier à la Rose, Arabella, Ariane à Naxos) bien sûr, et toujours Wagner (Senta, Sieglinde, Elisabeth, Eva).

UN SOUFFLE PUISSANT

Ce 14 février au soir, Nina Stemme a proposé un récital, comme elle sans ostentation, mais d'un goût original et sûr. Six des quelque 150 mélodies du compositeur danois Edvard Grieg, intimement liées à sa femme, la soprano Nina Hagerup, dont l'intense et poignant Cygne sur un poème d'Ibsen. Timbre opulent, projection généreuse, ligne pleine et souffle puissant, la voix de Nina Stemme est d'ambre chaud.

Dans les Wesendonck-Lieder, cette antichambre de Tristan, que Wagner composa en 1857-1858 sur des poèmes de Mathilde Wesendonck, qui fut la femme de son protecteur et sa maîtresse, le chant est admirablement tenu et conduit, avec une grâce et un modelé superbes. Interprète dans l'absolu, Nina Stemme préférera même dans "Im Treibhaus" tenir un aigu imparfait dans la nuance piano parce que le texte l'exige plutôt que de forcer la voix pour faire sortir le son. C'est une chanteuse caryatide, qui peut rattacher un escarpin doré avec le même naturel qu'elle arborera en deuxième partie une nouvelle et somptueuse robe Grand Marnier, qui lui donne des allures de Maréchale du Chevalier à la rose, un rôle straussien dans lequel elle excelle.

Cette fois, c'est du Finlandais Jean Sibelius que Nina Stemme a choisi les Cinq mélodies op.37 écrites dans sa langue maternelle, le suédois. Chants d'amour et mélancoliques ballades témoignent d'une inspiration au lyrisme soutenu. Enfin, six mélodies de Sergei Rachmaninov tour à tour ardentes, méditatives, véhémentes, enjouées, viendront conclure un récital que la pianiste française Bénédicte Haid a accompagné avec souplesse et délié.

Kurt Weill et Richard Strauss en bis. Que désirer de plus ?»

Não é para quem quer, mas antes para quem pode. E eu, por ora, não posso...

Antologia da lírica Pucciniana - I

(Manon Lescaut, EMI 50999 2 17420 9 5)

Manon Lescaut, uma obra de segunda linha, atinge a glória suprema, graças à prestação absolutamente antológica de dois monstros: Mattila, de uma envergadura dramática ímpar, compõe a protagonista definitiva, enquanto Giordani, de uma insolência vocal sem par (nos dias que correm...), cria o Des Grieux do século.

Não se pode querer mais, neste capítulo. É isto a felicidade.

Voltarei a este artigo, seguramente o primeiro a constar da coluna Best Of Operaedemaisinteresses'09.

domingo, 15 de fevereiro de 2009

Met, salas de cinema, velhos do Restelo e ovos de Colombo

Como grande amante de lírica, não posso ficar insensível a semelhante polémica. Evidentemente, a ópera deve ser assistida in loco, ossia em espaços concebidos para o efeito. Estádios de football e quejandos são palcos que devem permanecer fora do horizonte da lírica, correspondendo a territórios explorados de modo vil por um marketing ganancioso, próprio dos anos 1990 (vide Três Tenores), que algumas eminências pardas do universo lírico tão bem souberam aproveitar – Pavarotti, Domingo e Carreras.

Contudo, nesta polémica, devemos estabelecer, com clareza, uma linha que demarque o ideal do possível. Se parte dos opositores a esta experiência vivesse numa cidade como Lisboa - cuja ópera se afunda em merda, mais e mais, a cada dia que passa -, rapidamente perderiam o pudor e pergaminhos, abraçando com entusiasmo a possibilidade de assistir a uma récita de qualidade, ainda que numa sala de cinema!

Posto isto, eis os argumentos, pró...

«The dissenters say that the movement will lead to more conservative programming; that the voice will become subservient to appearance; that listeners will be trained to hear something electronic and lose an appreciation for a live experience.

Some worry that vocal training will change, de-emphasizing the ability to project, and that the Met’s effort is a deal with the Devil, because it will divert audiences from local opera houses to make the easier, cheaper trip to the mall.»

...e contra:

«The HD broadcasts have had a concrete effect on one area: acting. Singers are now aware that at any moment a live shot can frame them. Every bead of sweat, flap of the tongue, crooked tooth and quiver of the lip is on view.

“It changes the rules of engagement for singing and acting,” said Stephen Wadsworth, an opera director and opera acting teacher, who said he had noticed a surge in invitations to teach acting master classes.

Singers now worry about matters that are usually invisible to house audiences, like spraying saliva when singing consonants, or showing the effort to hit a high note, or turning upstage to clear one’s throat, or winking in support of a duet partner during a clinch, said Susan Graham, the mezzo-soprano, who has hosted several broadcasts and played Marguerite in the broadcast of Berlioz’s “Damnation de Faust.” The camera’s unrelenting nature means fewer peeks at the conductor.

“Sometimes opera is not an up-close spectator sport,” Ms. Graham said.

Acting in front of live cameras must not stop with the singing, she added. When a tenor croons of love, the soprano must show the fervor, because a camera may go for a reaction shot. Even the makeup is different, less exaggerated.

“We go the extra mile with realism,” Ms. Graham said.

The HD broadcasts have also created a new topic of conversation among singers: “ ‘Did it make me look fat?’ ” Ms. Graham said. “We are not unvain.”»

Falam de barriga cheia, os velhos do restelo, como sempre.

Peter Gelb, uma vez mais, descobriu o ovo de colombo, com este golpe certeiro.

Milk & Tosca

(cartaz de Milk, de Gus van Sant)

O que menos apreciei em Milk foi, indubitavelmente, a mediocridade da Tosca.

No filme, amiúde, são passados excertos daquela ópera de Puccini. Perto do epílogo, o protagonista assiste a uma récita da dita ópera, com uma encenação inenarrável, uma protagonista horrenda e um Scarpia de apedrejar.

Nem a referência a Bidú Sayão (sublinho o til, pois a senhora era brasileira!) – primadonna do Met no segundo quartel do século XX, pucciniana de antologia – salva a vergonha da referida Tosca.

(Bidú Sayão)

Já agora... o paralelismo Tosca – Harvey Milk é tão óbvio, quanto despropositado, não?!

Wiener Staatsoper

Lá para meados de Abril, por força de O Barbeiro de Sevilha (com Didonato...), Parsifal (com Seiffert como protagonista), A Italiana em Argel (com D'Arcangelo & Flórez...) e O Cavaleiro da Rosa.

Veremos, veremos, com prudência, muita prudência...

quarta-feira, 11 de fevereiro de 2009

terça-feira, 10 de fevereiro de 2009

Last Days (Gus Van Sant)

Kurt Cobain (1967-1994), líder dos Nirvana, animou parte significativa da minha geração. Para o bem e para o mal, sem pudor algum, confesso que, nem a criatura, nem a sua criação me impressionaram. De notar que, à época, a lírica, para mim, era ainda um território infimamente conhecido...

Assisti a este filme, há muito pouco tempo, movido pelo interesse que a figura de Cobain suscitara junto da maioria dos meus amigos.

Além de Kurt Cobain ser um borderline – impulsivo, instável e autodestrutivo – pouco mais sei da desafortunada história do músico. Da sua música, ainda menos...

A obra de Gus Van Sant Last Days, inspirada nos derradeiros dias de Cobain, é pouco interessante e dispensável, apenas tendo um mérito reconhecido: coloca a tónica da problemática do líder Cobain na dissociação psicótica, e não na equação depressão – suicídio.

A figura do músico, magistralmente desenhada e interpretada (Michael Pitt), surge envolta num universo autista, bizarro e discordante, em quase total ruptura com a realidade circundante. A casa onde a acção tem lugar – um óbvio prolongamento / espelho da realidade psíquica do protagonista – exibe uma degradação e despojamento plenamente conseguidos. Quanto ao resto...

(Kurt Cobain)

Para os fans de Cobain & Nirvana (!?), apenas.

segunda-feira, 9 de fevereiro de 2009

Plácido vs Maria - Adriana Lecouvreur - Met Opera House

Quinze anos após a última revival da bafienta produção dos anos 1960, eis que Adriana Lecouvreur volta a ver a luz do dia, no Lincoln Center.

Sem surpresa, a protagonista Guleghina roça o desastre, vocalmente, compondo o ramalhete por via da sua habilidade dramática.

Pelo que julgo saber, o papel demanda um soprano lírico. Maria Guleghina é um soprano cavernoso, berra que se farta, tem uma técnica desastrosa e um vibrato horrendo.

Nos antípodas desta prestação, Domingo ossia o eterno, brilha sem cessar...

«The Ukrainian soprano Maria Guleghina sings the title role, opposite Plácido Domingo as Maurizio, the role of his Met debut 40 years ago. Ms. Guleghina brings her trademark vocal and dramatic intensity to her work. Yet the music also calls for a soprano with Italianate legato and creamy lyricism. Ms. Guleghina sings with fervor and honorably tries hard to shape phrases with subtlety and nuance.

But in recent years she has been tearing with abandon into weighty Verdi roles like Lady Macbeth, and these days her sound is often grainy and hard edged. One missed the melting lyricism that should pervade the alluring aria “Io son l’umile ancella,” in which Adriana explains to her colleagues that as an actress, she is merely the servant of the creative spirit.

At that 1968 debut Mr. Domingo sang Maurizio opposite Tebaldi, no less. Now 68, he remains a wonder of vocal longevity. He missed the dress rehearsal because of a cold and took time to clear his throat and warm up during the performance on Friday. But soon he was singing with vigor, stylistic insight and ringing top notes. Some of the music was transposed down to suit Mr. Domingo’s current comfort zone. “That’s cheating,” purists might complain. But the trade-off is a Maurizio sung by a major tenor who still sounds like one.»

(Domingo e Guleghina, em Adriana Lecouvreur, de Cilea, Metropolitan Opera House)

Gérard Mortier

domingo, 8 de fevereiro de 2009

Billie Holiday – um (curtíssimo) olhar psicanalítico

(Billie Holiday)

Filha de um pai ausente, em nada me surpreende a estratégia seguida pela artista para reparar tal facto indelével: faz-se violar e, de modo compulsivo, oferece-se a inúmeros homens, por via da prostituição.

A estratégia terá a marca incontornável da perversão, mas o desejo latente, esse, é pueril e legítimo. Billie procura incessantemente o pai abandónico, entregando-se a um jogo masoquista: o pai ausente, maltratante, vai sofrendo metamorfoses – violador, cliente sexual, etc.

A relação com o materno, altamente problemática – inúmeras rupturas, abandonos, cuidados descontinuados -, ao invés de reparar a ausência já descrita, acentua-a, perpetuando-a. Os comportamentos adictivos – álcool e drogas – surgem como estratégias anti-depressivas, obviamente visando contrariar os terríveis sentimentos de abandono e incompletude.

Uma vez mais, o masoquismo expressa-se e triunfa na destrutividade auto-dirigida. Em lugar de odiar o mau objecto abandónico (materno e paterno), Billie deflecte a agressividade sobre si própria, suicidando-se.

Puta de vida...

sábado, 7 de fevereiro de 2009

Disse-me um passarinho...

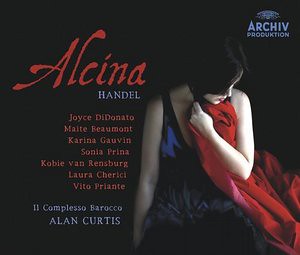

Falstaff (Verdi), com Plinska, Freni, Horne, Bonney, Graham e Lopardo, live from Met; Madama Butterfly (Puccini), com Gheorghiu e Kaufmann; Alcina (Handel), com Didonato, dirigida por Curtis e Semele (Handel), com Bartoli & Cª, dirigidos por Christie.

Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky): Matropolitan Opera House - 2007

Não pretendendo rivalizar com as belíssimas fotos da actual produção, eis as minhas (possíveis, péssimas) da revival de 2007, com Hvorostovsky, Fleming e Vargas, dirigidos por Gergiev:

nota: por lapso (meu!), a data que figura em algumas das fotografias não corresponde à verdade.

quinta-feira, 5 de fevereiro de 2009

Technorati: autoridade 20!!!

Eu sei, eu sei que, para o bem e para o mal, o narcisismo deste escriba se contenta com pouco.

Desde quando a ópera e a psicanálise interessam às gentes?!

quarta-feira, 4 de fevereiro de 2009

Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky): Matropolitan Opera House

Há um bom par de anos, no Met, tive a felicidade de assistir a uma récita de Eugene Onegin, encenada por Robert Carsen, com um elenco absolutamente luxuoso: Hvorostovsky, Fleming e Vargas.

Na presente temporada, a magnífica encenação de Carsen foi retomada, contando com outros intérpretes, não menos brilhantes: Hampson e Mattila.

Um leitor atento, que muito prezo, teve a amabilidade de me enviar este link com a crítica da récita. Claro está, já a havia lido...

«Doubt no longer. On Friday, when the Met brought back Robert Carsen’s beautifully spare 1997 production of “Eugene Onegin,” Ms. Mattila sang her first Tatiana at the house and was a revelation. Onegin remains a good role for the veteran baritone Thomas Hampson, who subtly conveyed the hauteur of the entitled, clueless hero. The fast-rising Polish tenor Piotr Beczala brought his bright, healthy voice and impassioned delivery to the role of Lenski, Onegin’s decent but fatally hotheaded friend, who is engaged to Tatiana’s winsome sister, Olga, here the dusky-toned mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk. And Jiri Belohlavek conducted a performance that deftly balanced urgency and lyrical languor.

But Ms. Mattila is the standout. In her luminously sung performance, she uncannily reveals the turmoil of a young woman who courageously, however recklessly, acts on her feelings. From the opening of the Letter Scene in Act I, when Tatiana is ushered to bed by Filippyevna, the hearty old family nurse, Ms. Mattila was like a hopelessly love-struck adolescent. Fidgeting under the covers, unable to sleep, she got up, twisted herself into a bundle of limbs and sat on the mattress, riveted by Filippyevna’s story of her marriage: an arranged union, naturally. The mezzo-soprano Jane Shaulis (replacing Barbara Dever, who was ill) made a charmingly bossy nurse.

When Tatiana rashly expresses her overwhelming feelings in a letter to Onegin, whom she has just met, Ms. Mattila brings burnished richness and aching expressivity to the fitful and inspired music. Onegin responds in person, thanking Tatiana for her charming candor, but dismissing marriage as too confining an institution for him. Here Mr. Hampson captured Onegin’s patronizing decorum in advising Tatiana to be more cautious about confiding herself to men who may not be so discreet. Here Ms. Mattila was the image of abject humiliation, singing with halting poignancy, looking like a stoop-shouldered, guilty child.

In the final scene, years later, when Onegin re-encounters Tatiana, now married to the older, decent and devoted Prince Gremin (the sturdy bass Sergei Aleksashkin), Mr. Hampson was the embodiment of a young man who realizes too late what a haughty fool he was to have dismissed Tatiana’s feelings as some schoolgirl crush. Filling the phrases with desperation, he sometimes pushed his voice too forcefully. Over all, though, his singing was sensitive, robust and elegant.

In the crushing final scene, Tatiana, honoring her marriage vows, rejects Onegin’s pleas while admitting that her feelings for him remain. They had a brief chance to achieve truly romantic love. She took a risk, he let it slip. “We were so close,” Ms. Mattila sang, with a wistful beauty that will stay with me. »

domingo, 1 de fevereiro de 2009

Norma(líssima)...

Ousar incarnar a protagonista de Norma (Bellini) é como almejar o céu. Não que as pretéritas protagonistas de referência – cronologicamente: Ponselle, Cigna, Callas, Sutherland e Caballé – fossem isentas de mácula!

Felizmente, não pertenço aos que idealizam as prime donne de outrora...

Em boa verdade, discordo dos que fixaram na figura de Isolda (Tristan und Isolde) o papel feminino supremo, pela exigência dramática e de meios. Norma é, para mim, O papel.

Norma requer um domínio técnico ímpar – agilidade e extensão invulgares -, resistência e volume, a par de habilidades dramáticas reconhecidas.

Na versão de concerto de Norma, que a FCG integrou no ciclo Heroínas Trágicas da Antiguidade, Silvana Dussmann atreveu-se a abordar a protagonista da ópera. Ousou, arriscou e estatelou-se ao comprido...

Dussmann será uma intérprete esforçada e empenhada mas, como cantora, roça a mediania. Faz uma incursão no belcanto, ignorando a sua essência! Não sabe a dita senhora o que é respeitar a linha melódica, desenhar arcos belos e graciosos, ornamentar... Ao invés, a senhora Dussmann revela sérios problemas de afinação, estridência e uma falibilidade na coloratura confrangedora.

Começou péssima - uma Casta Diva de feira (o final da cabaletta merecia um apupo!) -, depois lá se aguentou, não deixando de conspurcar o notável trabalho de dois dos demais solistas, Botha e Brunner.

Heidi Brunner concebeu uma Adalgisa muito respeitável e digna. Muito disciplinada (sobretudo no acto I, é certo...), abrilhantando o dueto com Pollione, claramente o momento maior da récita, na minha opinião.

O Pollione de Botha, antes de mais, deu-me uma valentíssima bofetada de luva branca. Sempre o desprezei, apoiando-me em (algumas, por certo!) prestações sofríveis que me proporcionou, a maior das quais – hélas - como Pollione, há exactamente dez anos.

Indubitavelmente o melhor intérprete da récita, Botha revelou pujança, técnica, talento interpretativo e ousadia. Com agudos certeiros e volume generoso, brindou-nos com uma entrada triunfal – Meco all'altar di Venere -, embelezou o dito dueto com Adalgisa, sobressaindo no terceto que encerra o acto I.

Do Oroveso de Kotchinian, pouco haverá a enaltecer, para alem de um timbre interessante, que se foi abafando e extinguindo...

Foster não deixará memória na direcção desta Norma, orquestralmente rotineira e insípida.

(Giuditta Pasta, a prima Norma)

Termina assim o ciclo (ousado e atrevido, mas louvável) proposto pela FCG - Heroínas Trágicas da Antiguidade -, que havia começado com chave de ouro, com uma Elektra de antologia, tendo sido maculado por uma Medée olvidável.