Ópera, ópera, ópera, ópera, cinema, música, delírios psicanalíticos, crítica, literatura, revistas de imprensa, Paris, New-York, Florença, sapatos, GIORGIO ARMANI, possidonices...

sexta-feira, 30 de setembro de 2011

quarta-feira, 28 de setembro de 2011

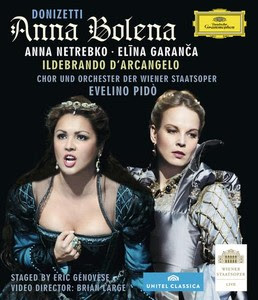

Anna Bolena: première no Met - 26 de Outubro de 2011

«To open the Met’s season, Ms. Netrebko sang the punishing title role of Donizetti’s “Anna Bolena” in the company’s first production of this breakthrough Donizetti work from 1830. The extended last scene was the high point of Ms. Netrebko’s performance as the distraught British queen (based on the historic Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII). Having been falsely condemned for betraying her husband, Anna drifts in and out of sanity.

Ms. Netrebko sang an elegantly sad aria with lustrous warmth, aching vulnerability and floating high notes. When the audience broke into prolonged applause and bravos, Ms. Netrebko seemed to break character and smile a couple of times, though her look could have been taken as appropriate to the dramatic moment, since the delusional Anna is lost in reverie about happy days with her former lover.

Then, at the end of this “Mad Scene,” Anna, restored to horrific reality, curses the “wicked couple,” the king and his new queen, and stalks off to her execution, insisting implausibly that she is not seeking divine retribution but going to her grave with mercy on her lips. Ms. Netrebko dispatched Donizetti’s cabaletta, all fiery coloratura runs and vehement phrases, with a defiance that brought down the house.

Yet Ms. Netrebko’s Anna and the overall performance of the opera were not what they could have been. The production, by the director David McVicar, is uninventive and safe. The sets, by Robert Jones (in his Met debut), are handsome and efficient but tamely traditional, using a matrix of rotating white brick walls and sliding wood panels to evoke the interiors and environs of Henry’s palaces.

In Act I, when the king’s hunting party gathers, complete with two impressively large dogs, a bit of abstraction is introduced through some sculptural gray trees. Jenny Tiramani’s costumes are colorful, detailed and true to the period. Too true. This Henry could have come from the set of almost any of the innumerable films and television shows that have been made about the Tudors.

But the bigger problem was Marco Armiliato’s routine conducting. Mr. Armiliato has been valuable to the Met’s Italian repertory wing since his 1998 house debut. In “Anna Bolena” he conveyed an understanding of bel canto style, in which arching lines must be given room to spin and cast their spell, and accompaniment patterns have to be flexible.

The singers seemed to feel supported by Mr. Armiliato, who was always there when they took liberties. That was the problem. This performance needed a conductor to instill some intensity into the music, to keep the cast more on edge, especially in the early scenes. Much of the action occurs in highly charged bursts of dramatic recitative. But too often here the orchestra chords that buttress the vocal lines were listless. And the orchestra’s playing lacked character.

Previously, Ms. Netrebko had sung the role of Anna only at the Vienna State Opera this spring. She started tentatively on Monday, perhaps settling in for the long, hard night of singing that awaited her. She looked regal and splendid. And in a nice directorial touch, Anna first appeared with a little red-haired girl, clearly her daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth.

At 40, Ms. Netrebko may be in her vocal prime. Her sound is meltingly rich yet focused. Sustained tones have body and depth. Her contained vibrato exposed every slight slip from the center of a pitch, especially in midrange, but I’m not complaining. This remains a major voice, with resplendent colorings and built-in expressivity.

Bel canto purists have long debated whether Ms. Netrebko is a natural to the style, especially in her execution of coloratura passagework. She may not have the nimble precision exemplified by Beverly Sills (who was criticized by some for that very accuracy). Ms. Netrebko’s approach is to sing coloratura as a lyrical elaboration of the vocal line, which she did affectingly as Anna. And she exudes vocal charisma.

Still, at moments throughout the evening her singing seemed cautious. She was at her best when sparring with other singers, especially the mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Gubanova, who was Giovanna (the queen’s lady-in-waiting Jane Seymour, though it’s best to stick to the Italian names, since “Anna Bolena,” with a libretto by Felice Romani, plays very loose with history). Ms. Gubanova has an ample, dark voice with a slightly hard-edged quality that takes some adjusting to. She sang Giovanna with incisive delivery, folding embellishments and runs into impassioned vocal lines.

Her character was a bundle of nerves in Donizetti’s inspired Act II scene in which Giovanna finally confesses to the queen that she has been the king’s mistress and will become his new wife. Again the orchestra under Mr. Armiliato seemed to hold back, rather than empower, the intensity these two artists were trying to summon onstage.

The bass Ildar Abdrazakov brought his earthy, muscular voice to the role of Enrico (Henry VIII). Though his passagework was muffled by his gravelly tones at times, he was an imposing presence, and he did not overplay the king’s brutishness.

The tenor Stephen Costello won a hearty ovation for his Riccardo (Lord Percy, Anna’s former lover). This was a big assignment for the gifted and game young tenor. Mr. Costello captured the character’s consuming adoration for Anna through his impetuous and anguished singing.

The role includes a touchstone tenor aria, “Vivi tu,” in which the condemned Riccardo implores his friend Lord Rocheford (Anna’s brother, here the solid bass-baritone Keith Miller) to evade the king’s wrath and go on living. Mr. Costello mostly navigated the music’s demanding passagework and exposed high notes. To hear this rising artist stretching himself was part of the excitement.

The mezzo-soprano Tamara Mumford took on the trouser role of Mark Smeaton, a court musician with a fatal crush on Anna. Her singing was sometimes shaky but always honest and ardent. The able tenor Eduardo Valdes as the court official Hervey rounded out the cast. Every role is significant in an opera so rich with ensembles, including a climactic Act I sextet almost as memorable as the enduring sextet from Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor,” and more contrapuntally intricate.

Mr. Gelb has said that ideally the Met should make an artistic statement by presenting an ambitious new production every opening night. Two years ago he took a chance on Luc Bondy’s ill-conceived staging of Puccini’s “Tosca.” Last season came the premiere of Robert Lepage’s production of Wagner’s “Rheingold,” which is still being argued over, as audiences await the last two installments of the complete “Ring” cycle this season.

“Anna Bolena” represented a different sort of risk. To make a case for this great, overlooked opera, a company must have a stellar soprano in the title role. Ms. Netrebko is that artist. If only she and her colleagues onstage had received more help from Mr. McVicar and Mr. Armiliato.

The gala evening performance was relayed to Times Square and to Lincoln Center Plaza, where there was seating for some 3,000 people who had scooped up free tickets earlier. After the curtain calls onstage, the “Anna Bolena” cast appeared on the Met’s outdoor balcony to the cheers of the crowd. This is becoming a welcome tradition under Mr. Gelb.»

Ao que parece, a menina-dos-olhos de Peter Gelb - Netrebko - compôs uma Anna Bolena modelar. Brilhou como poucos. Da encenação, pouco haverá a enaltecer, dada a irresistível incursão de McVickar pelo pró-realismo... Armiliato também não se encontrava particularmente inspirado...

segunda-feira, 26 de setembro de 2011

Anna, Anna!

(Anna Netrebko... ossia Anna Bolena)

A Catedral abre amanhã a temporada 2011 – 2012 com uma nova produção de Anna Bolena (Donizetti). Jamais o Met assistiu a esta peça lírica, que se estreia por via da glamourosa Netrebko.

Entretanto, aguardamos pela récita de Outubro, que o Ministério da Cultura difunde em directo, em HD!

sábado, 24 de setembro de 2011

Maria... Gheorghiu!

Gheorghiu decide, neste registo, homenagear a suprema Diva, A Callas... Homenagear Maria Callas? O nobre gesto de Angela oculta um desejo – narcísico, necessariamente – de identificação com a Grega.

Desde há muito tempo que Angela Gheorghiu aspira ao estatuto de suma diva. Nas entrevistas, declarações e gestos, a romena revela uma apetência e fascínio por aspectos menos afins com a artistry, e obviamente mais mundanos.

No essencial, diria que Gheorghiu se sobrestima. Trata-se de uma notável intérprete, com rasgos vocais relevantíssimos. Testemunhei a qualidade maior da sua Violeta Valery, que me esmagou. Como a Grega, Angela Gheorghiu é, também, uma magnífica Tosca. As afinidades de reportório das duas ficam-se por aqui... Outras afinidades? Claro que as há: ambas enfermam de um narcisismo frágil, sucessivamente camuflado com soberba e demais defesas compensatórias.

A seu tempo, avaliaremos a qualidade desta homenagem.

domingo, 11 de setembro de 2011

Salvatore Licitra, RIP (1968 - 05.09.2011) - II

(Salvatore Licitra)

Não tive muitas ocasiões para assistir, live, às performances de Licitra. Recordo, contudo, o seu Manrico, em Lisboa, em 2002. À época, as expectativas eram elevadíssimas, mas foi a Leonora de Katia Pellegrino quem mais me impressionou... O Manrico de Licitra brilhou, sem dúvida, mas faltou-lhe a cereja! Doravante, não tive mais encontros com o desafortunado Salvatore.

Contudo, parece-me injusta e imprecisa a identificação de Licitra com Pavarotti! O segundo era, sobretudo, um belcantista, que tarde enveredou pela linha verdiana. Licitra – esse – era um lírico-spinto.

A identificação de um com o outro decorre – penso – da substituição de Pavarotti por Licitra, na célebre récita de Tosca – no Met -, que marcou a afirmação explícita de Salvatore Licitra.

Que descanse em paz...

Italia, su patria sentimental, lo conoció en el año 2000. Riccardo Muti dirigía a la orquesta desde el pódium de la Scala de Milán y sobre el escenario todo estaba preparado para una Toscamás. Pero salió un tenor diferente, una voz que los milaneses no habían escuchado nunca, y desde entonces Italia sintió un especial apego por Salvatore Licitra, un cantante al que muchos han visto como el heredero de Luciano Pavarotti, muerto en 2007. El debut en la Scala se había producido un año antes, también de la mano de Muti, con una versión de Il Trovatore avalada por el director que dividió a la platea en sorprendidos y ofendidos.

Licitra pudo confirmarse como uno de los cantantes italianos más interesantes del momento cuando el mismo Pavarotti le dio su oportunidad dos años después. De nuevo se representaba Tosca, esta vez en el Metropolitan de Nueva York, pero con un reparto capitaneado por Luciano Pavarotti. Sin embargo, la suerte quiso que el gran tenor italiano no pudiese enfundarse el traje bohemio del pintor Mario Cavaradossi por una indisposición, y a Licitra le llegó su momento. El joven tenor dio a la ópera de Puccini un toque humano, destapó las emociones de una ópera romántica representada hasta la saciedad y los neoyorquinos supieron ver en él un sustituto a la altura. Una vez terminada la función, el público del Met le dedicó una ovación de varios minutos.

Los veroneses tampoco le olvidan. Allí debutó en 1998 en el festival que cada año viste de teatro la Arena di Verona, y en el que interpretó por sorpresa la ópera de apertura del festival. La elección esta vez fue Un ballo in maschera, obra que le había hecho subirse a los escenarios meses antes en el Teatro Regio de Parma. Verona, que siempre ha tenido una relación estrecha con la música de Verdi y con la ópera más clásica, le dio la confianza necesaria para que, años después, supiera afrontar la Tosca de la Scala.

Uno de los que más ha sentido la muerte del tenor, por ser más amigo que compañero de Licitra, ha sido el director Riccardo Muti. Inmerso en una gira con la Chicago Symphony Orchestra, el director italiano ha recordado desde Viena al tenor. "La noticia de la prematura marcha de Salvatore Licitra me tiene consternado. Era un artista que al que me ligaba una afectuosa amistad madurada en muchísimas colaboraciones en el teatro y en algunas grabaciones", ha comentado Muti a Il Corriere de la Sera.

sábado, 10 de setembro de 2011

Mid-price :)

Nem tudo serão rosas, por estas bandas da reedição. Uma Norma dépassée, um Hänsel und Gretel de segunda escolha e um Don Giovanni irregularíssimo. Mas como resistir a Os Troianos de Dutoit ou a Fedora, interpretada por Olivero? Os fãs de Dame Joan Sutherland irão regozijar com Esclarmonde. Quanto aos mozarteanos – onde me encontro -, creio que poderão regalar-se com o melhor Così da era digital.

É aproveitar esta reedição mid-price!

segunda-feira, 5 de setembro de 2011

Salvatore Licitra, RIP (1968 - 05.09.2011)

quarta-feira, 31 de agosto de 2011

segunda-feira, 29 de agosto de 2011

domingo, 28 de agosto de 2011

Bayreuth - III - Tannhäuser (as fotos)

Bayreuth - II - Tannhäuser

Absolutamente pervertido, o Tannhäuser de Sebastian Baumgarten foi apupado do princípio ao fim! Segundo consta, a liberdade da encenação confundiu-se com uma obra grotesca, nos antípodas da concepção de Wagner.

Perversão metafórica em Bayreuth, evidentemente, mas não só... Para detalhes mais sórdidos, sugiro uma leitura atenta da critica de Mark Ronan, como segue.

sábado, 27 de agosto de 2011

Destinos Dissolutos

Por motivos de agenda, as deslocações da família Dissoluta à Casa Mãe encontram-se suspensas. Para mais, odiamos furacões, que são uma grande maçada!

Desta feita, dada a excelsa qualidade da nova produção de Don Giovanni (encenação de Carsen), no alla Scala, aí vamos nós, para uma récita de sonho, a 16 de Dezembro de 2011.

Aos que desejarem, endereço convite para partilharem o nosso camarote!

Afinal de contas, juntar, numa produção, Terfel, D’Arcangelo, Netrebko, Filianoti, Frittoli e a direcção de Barenboim...

Vão-se as pratas, fiquem os lingotes de ouro!

quinta-feira, 25 de agosto de 2011

Narciso Ceausescu

(Nicolae Ceausescu)

A Autobiografia de Nicolae Ceausescu é um notável documentário de Andrei Ujica, integralmente concebido com imagens da propaganda romena.

O filme retrata a ascensão e queda do regime liderado por Nicolae Ceauscescu (1918-1989). Tendo início com a morte de Gheorghiu-Dij e transmissão do poder ao seu sucessor “dinástico”, culmina com o julgamento sumário de Nicolae e sua mulher, Elena.

Recordo a morte do deplorável ditador e respectiva concubina, numa manhã de final de Dezembro de 1989, era eu um jovem adulto. Por ocasião do filme, temi que as impressionantes imagens do fuzilamento do casal fossem exibidas. Na época, correram mundo e chocaram-me profundamente.

Percebi que o gesto grotesco – a exibição dos troféus de caça – correspondia a uma prova fálica do triunfo, porventura reclamada por um povo oprimido e desejoso de vingança.

Inteligentemente, Ujica não embarca neste dificilmente resistível cliché!

Sempre nutri interesse pela personalidade de Nicolae Ceausescu. O seu despostismo (quase) ilimitado intrigava-me sobremaneira. Por esta razão, num movimento impulsivo, acorri à sala do Monumental, assim que soube da estreia do filme, hoje mesmo.

Evidentemente, a figura do ditator é omnipresente. O retrato que se observa é de um homem absolutamente fundido com o poder, reclamando em permanência gratificações narcísicas – a aclamação por parte do objecto (povo, colegas de ofício, nomenclatura, etc.), diante da sua suprema glória edificante (assaz megalómana), é transversal a toda a obra.

A personagem que as imagens reais revelam enferma de um narcisismo patético e caricatural, que a todo o instante exige do outro um reconhecimento das suas excelsas capacidades.

De permeio, deparamos com uma criatura profundamente desinteressante, roçando a rudeza. Embora frugal em público, no racato, a película revela um sábio culto aburguesado do ócio e demais prazeres capitalistas, sempre na companhia de Elena e restante séquito.

Imperdível!

A Autobiografia de Nicolae Ceausescu

Bayreuth - I

À semelhança dos demais festivais líricos – quiçá por força da crise – os ecos de Bayreuth escasseiam!

Contudo, a abc faz uma síntese do desastroso Tannhäeuser (nova produção), cuja encenação bordeja o lixo. Já no tocante a Lohengrin, outro galo canta, apesar da rataria…