Ópera, ópera, ópera, ópera, cinema, música, delírios psicanalíticos, crítica, literatura, revistas de imprensa, Paris, New-York, Florença, sapatos, GIORGIO ARMANI, possidonices...

segunda-feira, 28 de setembro de 2009

domingo, 27 de setembro de 2009

Da Era Gelb

(Peter Gelb, director-geral do Met)

A Era Gelb parace marcada pela ousadia e primazia da teatralidade, como segue:

«In his office a couple of weeks ago Mr. Gelb said the decision to open the new season this way, with a brand-new, pared-down production of an opera that was a trademark of the old Met, was “not an accident.” His self-proclaimed mission from the beginning has been to revivify an institution whose core audience he thinks is rapidly aging itself to extinction, by re-emphasizing opera’s theatricality.

Mr. Gelb is married to the conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson and has two children from a previous marriage. His day sometimes begins as early as 4 or 5 a.m., when he checks his e-mail and gets on the phone to Europe. On Monday he was on the job until well after midnight. Wearing a black shirt and velvet tuxedo jacket, he held between-act receptions in his office for friends, family, people from the art and the theater worlds and even the president of Finland. (Karita Mattila, who played Tosca, wearing brown contact lenses, is a Finn.) After the second act he and Mr. Bondy also fussed backstage over the timing and light cues for Tosca’s leap.

sábado, 26 de setembro de 2009

O Triunfo da Barroca

Uma voz cristalina, magra e elegante, quase sem vibrato, de uma beleza imensa.

Graciosa e feminina, pueril e diáfana, a magnífica Kozena triunfa no barroco, brilhando no lirismo e bravura (esta última, habitualmente estranha às suas habilidades).

À agilidade vivaldista da Bartoli, Magdalena Kozena responde com uma elegância lírica sem paralelo, na actualidade, coadjuvada por uma orquestra sumptuosa, rica na ornamentação, certeira, e poética na expressão.

E para quê mais palavras?

___________

* * * * *

(5/5)

Da Isolda

Eis algumas interessantes considerações sobre o papel dos papéis de soprano:

«"Isolde is a severe test for the voice," the Norwegian soprano Kirsten Flagstad – Isolde on the famous recording under Wilhelm Furtwängler – once observed. "Either it can be completely destroyed, or it can grow, as mine did." But Isolde is a great acting part, too. "It isn't all loud and screamy like the stereotypes," says Bullock. "It's a Shakespearean role, really."

Not surprisingly, many sopranos are nervous when the idea of Isolde is first mooted. In the 90s, the late Sir Georg Solti asked American soprano Renée Fleming if she would sing the role for a production he was planning. Fleming looked at the score, decided that her voice would never be the same, and refused. A generation earlier, Dame Margaret Price was persuaded to sing Isolde for a recording under German conductor Carlos Kleiber. The result, made up from several takes, is one of the most outstanding recorded Isoldes. Efforts to tempt Price to do Isolde on the stage, however, never came to anything. "I'm not a long-distance runner," she insisted. "I'll sing it to my dogs."

Price's performance has had lasting effects on today's Isoldes. Before her, the role belonged to sopranos such as Flagstad and the late Birgit Nilsson, massive of voice, with a laser-like precision of tone. Price came from another, more Italianate vocal tradition. Bullock says: "Isolde wasn't something I was thinking of until I was asked. But listening to Price made me realise it could be done. I think if I had started by listening to Nilsson I would have committed suicide."

Stemme adds: "I thought my first offer of Isolde was a joke." Stemme, at that time, was more a lyric Mozartian singer than a dramatic Wagnerian. "But a seed was planted. I went away and studied the role and realised it would be possible."

The role can certainly take its toll on a soprano's voice. As a young woman, the Scottish soprano Linda Esther Gray won great acclaim for her exceptional interpretation of the role under the renowned Wagnerian conductor Reginald Goodall for Welsh National Opera in the 70s. But Gray was rarely the same singer afterwards and her career was sadly cut short. The fine Viennese singer Helga Dernesch was another whose career struggled to recover from Herbert von Karajan's decision to cast her as Isolde in performances and on record in the 70s.

But if Isolde can be unforgiving it can also be incomparably rewarding. If there is one singer whom today's Isoldes revere more than any other, it is the Berlin-born soprano Frida Leider, who dominated the role in the interwar years. "Ah, Leider, she is the winner," says Stemme. "She's got it all." Evans agrees: "There's never just one way of doing anything. But it's the vibrancy of her sound that marks Leider out. All those colours in the voice."

Leider's recordings – sadly only of excerpts from the opera – point a path to the heart of the role. In her autobiography, Leider explains with great clarity how she approached Isolde. "I always tried to sing in the Italian bel canto style, and above all, I endeavoured to incorporate this style into my Wagner interpretations. I put my enunciation under the microscope. I accentuated very sharply but tried to do this while sustaining my vocal line."

It all sounds so simple. But it is the key to climbing the Wagnerian Everest and surviving to do it all over again a few nights later. Isoldes of this class are rare. Price came close, but only in the recording studio. The late Hildegard Behrens, who made an extraordinary recording of the opera under Leonard Bernstein, was probably the best of the rest in recent times. Now though, there is another name to add to the list. When I ask Evans to name her favourites, she replies: "First Leider, then Behrens – and now Nina Stemme," she responds. "I think she is very special."»

Pela parte que me toca, além das clássicas, que se estenda um longo tapete vermelho às Senhoras Stemme, Voigt e Meier - todas elas no activo. E quem nunca viu a Isolda da Stemme, verdadeiramente, nunca tomou contacto com a plenitude wagneriana...

Stemme é a minha Isolde, sem rival alguma - e conto com cerca de uma quinzena das maiores da história!

A POLÉMICA ESTÁ INSTALADA... CHOVAM OS COMENTÁRIOS!!!

(Nina Stemme, como Isolde - Glyndebourne)

«"Isolde is a severe test for the voice," the Norwegian soprano Kirsten Flagstad – Isolde on the famous recording under Wilhelm Furtwängler – once observed. "Either it can be completely destroyed, or it can grow, as mine did." But Isolde is a great acting part, too. "It isn't all loud and screamy like the stereotypes," says Bullock. "It's a Shakespearean role, really."

Not surprisingly, many sopranos are nervous when the idea of Isolde is first mooted. In the 90s, the late Sir Georg Solti asked American soprano Renée Fleming if she would sing the role for a production he was planning. Fleming looked at the score, decided that her voice would never be the same, and refused. A generation earlier, Dame Margaret Price was persuaded to sing Isolde for a recording under German conductor Carlos Kleiber. The result, made up from several takes, is one of the most outstanding recorded Isoldes. Efforts to tempt Price to do Isolde on the stage, however, never came to anything. "I'm not a long-distance runner," she insisted. "I'll sing it to my dogs."

Price's performance has had lasting effects on today's Isoldes. Before her, the role belonged to sopranos such as Flagstad and the late Birgit Nilsson, massive of voice, with a laser-like precision of tone. Price came from another, more Italianate vocal tradition. Bullock says: "Isolde wasn't something I was thinking of until I was asked. But listening to Price made me realise it could be done. I think if I had started by listening to Nilsson I would have committed suicide."

Stemme adds: "I thought my first offer of Isolde was a joke." Stemme, at that time, was more a lyric Mozartian singer than a dramatic Wagnerian. "But a seed was planted. I went away and studied the role and realised it would be possible."

The role can certainly take its toll on a soprano's voice. As a young woman, the Scottish soprano Linda Esther Gray won great acclaim for her exceptional interpretation of the role under the renowned Wagnerian conductor Reginald Goodall for Welsh National Opera in the 70s. But Gray was rarely the same singer afterwards and her career was sadly cut short. The fine Viennese singer Helga Dernesch was another whose career struggled to recover from Herbert von Karajan's decision to cast her as Isolde in performances and on record in the 70s.

But if Isolde can be unforgiving it can also be incomparably rewarding. If there is one singer whom today's Isoldes revere more than any other, it is the Berlin-born soprano Frida Leider, who dominated the role in the interwar years. "Ah, Leider, she is the winner," says Stemme. "She's got it all." Evans agrees: "There's never just one way of doing anything. But it's the vibrancy of her sound that marks Leider out. All those colours in the voice."

Leider's recordings – sadly only of excerpts from the opera – point a path to the heart of the role. In her autobiography, Leider explains with great clarity how she approached Isolde. "I always tried to sing in the Italian bel canto style, and above all, I endeavoured to incorporate this style into my Wagner interpretations. I put my enunciation under the microscope. I accentuated very sharply but tried to do this while sustaining my vocal line."

It all sounds so simple. But it is the key to climbing the Wagnerian Everest and surviving to do it all over again a few nights later. Isoldes of this class are rare. Price came close, but only in the recording studio. The late Hildegard Behrens, who made an extraordinary recording of the opera under Leonard Bernstein, was probably the best of the rest in recent times. Now though, there is another name to add to the list. When I ask Evans to name her favourites, she replies: "First Leider, then Behrens – and now Nina Stemme," she responds. "I think she is very special."»

Pela parte que me toca, além das clássicas, que se estenda um longo tapete vermelho às Senhoras Stemme, Voigt e Meier - todas elas no activo. E quem nunca viu a Isolda da Stemme, verdadeiramente, nunca tomou contacto com a plenitude wagneriana...

Stemme é a minha Isolde, sem rival alguma - e conto com cerca de uma quinzena das maiores da história!

A POLÉMICA ESTÁ INSTALADA... CHOVAM OS COMENTÁRIOS!!!

(Nina Stemme, como Isolde - Glyndebourne)

sexta-feira, 25 de setembro de 2009

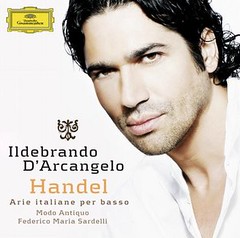

Ildebrando D'Arcangelo, Handel: Arias

The Independent dixit:

«Album: Ildebrando D'Arcangelo, Handel: Arias (Deutsche Grammophon) (Rated 3/ 5 ) Reviewed by Andy Gill Bass-baritone singers are generally deprived of the starring roles accorded their tenor colleagues. But "Brando" has enough of his namesake's smouldering good looks to make his mark with this debut solo anthology of Handel arias. Set to the period arrangements of Modo Antiquo, it's imposing stuff, with arias from Agrippina, Orlando and Rodelinda, a pair from Ariodante switching between wretched grief and exultant joy, and elsewhere a selection of hissing snakes, evil, darkness and terror, all wielded with an elegant grace occasionally bordering on the humorously knowing.»

«Album: Ildebrando D'Arcangelo, Handel: Arias (Deutsche Grammophon) (Rated 3/ 5 ) Reviewed by Andy Gill Bass-baritone singers are generally deprived of the starring roles accorded their tenor colleagues. But "Brando" has enough of his namesake's smouldering good looks to make his mark with this debut solo anthology of Handel arias. Set to the period arrangements of Modo Antiquo, it's imposing stuff, with arias from Agrippina, Orlando and Rodelinda, a pair from Ariodante switching between wretched grief and exultant joy, and elsewhere a selection of hissing snakes, evil, darkness and terror, all wielded with an elegant grace occasionally bordering on the humorously knowing.»

quinta-feira, 24 de setembro de 2009

La Figlia del Reggimento

Highlights da mesma ópera de Donizetti, interpretados pela bela Anna Moffo, na versão italiana da ópera:

Le Nozze di Susanna

(Danielle de Niese, como Susanna - As Bodas de Fígaro, Met Opera House -, à esquerda)

A estreia de Danielle de Niese no Met, como Susanna, parece ter sido marcada pelo sucesso.

Há uns anos, o registo handeliano da belíssima de Niese decepcionou-me muitíssimo...

Eis, em síntese, o essencial desta As Bodas de... Susanna:

«Most notably Danielle de Niese, a natural comic actress, in her first Met Susanna, brought an ebullient playfulness to the role, particularly in her scenes with Cherubino and the Countess. But she was not just a comedian; in her scenes with the Count she conveys the sense that beneath her flirtatiousness Susanna knows she is playing with fire and is constantly recalculating her moves.

Ms. de Niese’s lyric soprano has a good, solid top supported by a firm middle range that yields a full, if not especially loud, rounded tone that can be momentarily disconcerting if you expect the bright soubrette voice that has become the norm in this role. But Ms. de Niese recast Susanna in her own image and was at her most persuasive in her passionate account of “Deh! Vieni, non tardar,” in the final act.»

A estreia de Danielle de Niese no Met, como Susanna, parece ter sido marcada pelo sucesso.

Há uns anos, o registo handeliano da belíssima de Niese decepcionou-me muitíssimo...

Eis, em síntese, o essencial desta As Bodas de... Susanna:

«Most notably Danielle de Niese, a natural comic actress, in her first Met Susanna, brought an ebullient playfulness to the role, particularly in her scenes with Cherubino and the Countess. But she was not just a comedian; in her scenes with the Count she conveys the sense that beneath her flirtatiousness Susanna knows she is playing with fire and is constantly recalculating her moves.

Ms. de Niese’s lyric soprano has a good, solid top supported by a firm middle range that yields a full, if not especially loud, rounded tone that can be momentarily disconcerting if you expect the bright soubrette voice that has become the norm in this role. But Ms. de Niese recast Susanna in her own image and was at her most persuasive in her passionate account of “Deh! Vieni, non tardar,” in the final act.»

quarta-feira, 23 de setembro de 2009

Do Contra-tenor...

(da esquerda para a direita - Scholl, Daniels e Jaroussky )

Eis um rigoroso artigo sobre o tema:

«Au fait, qu'est-ce qu'un contre-ténor ? Peu de dénominations ont suscité autant de querelles d'experts ! Tout, d'ailleurs, a commencé par un malentendu. En 1943, le compositeur Michael Tippett entend à Canterbury un chanteur à la voix angélique, qui semble n'avoir pas mué : Alfred Deller. Il croit avoir retrouvé la trace de ce mystérieux «contre-ténor» qu'évoquaient Purcell et Bach. Deller, pourtant, ne revendique nullement ce titre : il se qualifie d'alto ! Autrement dit, la voix féminine grave. D'où vient la méprise ?

Klaus Nomi un contre-ténor à l'heure du rock

À l'époque baroque, le terme « contre-ténor » ne désigne pas une technique de chant, mais une ligne sur une partition : celle qui est au-dessus de la partie de ténor. Le terme le plus juste pour qualifier le type de voix ressuscité par Deller serait celui de «falsettiste», car il a recours à la voix de fausset, la «voix de tête». À ne pas confondre avec la «haute-contre», ténor aigu chantant en voix de poitrine ! Les falsettistes (ceux que nous appelons aujourd'hui «contre-ténors», vous suivez toujours ?) ont fleuri au début de l'époque baroque, mais ils ont progressivement disparu, remplacés au XVIIIe par les tout puissants castrats, et au XIXe par les ténors à la voix virile et puissante. Finie, la nostalgie du troisième sexe, fascination pour un corps d'homme produisant des sons de femme.

David Daniels. Bouleversant dans Theodora de Haendel.

Deller fut le premier à redécouvrir cette manière de chanter. Sa voix pure était délicate, plus appropriée aux chants religieux qu'à l'opéra. Mais dès les années 1950, l'Américain Russell Oberlin, montra que l'on pouvait être contre-ténor et acteur. Sa fragilité vocale (épine dans le pied des contre-ténors) ne résista pas à l'opéra, jusqu'à ce que l'Anglais James Bowman vienne montrer que le falsettiste pouvait avoir une voix puissante. La lame de fond de la musique baroque, dans les années 1970, fit éclore des générations de contre-ténors influencés par René Jacobs et son chant complet : voix de poitrine incarnée dans le grave, voix de tête éthérée dans l'aigu. Henri Ledroit, Gérard Lesne, plus tard Andreas Scholl suivirent cet exemple, tandis que l'extraterrestre Klaus Nomi mettait le contre-ténor à l'heure du rock.

Côté américain s'imposait une image virtuose et théâtrale du contre-ténor, loin de tous les clichés : David Daniels, Lawrence Zazzo, Bejun Mehta, sont ces bêtes de théâtre qui affrontent les personnages de guerriers des opéras de Haendel. Du moins quand on les leur confie : car leur ex-collègue Jacobs, devenu chef, s'est mis à soutenir qu'une mezzo soprano était plus appropriée ! D'ailleurs, quand Haendel ne disposait pas d'un castrat, ne recourait-il pas à une femme ? En revanche, le répertoire s'étend, car les compositeurs de notre temps se sont vite intéressés à cette voix : de Britten, avec Le Songe d'une nuit d'été, à Peter Eötvös, dont l'opéra Trois Sœurs est écrit pour trois contre-ténors.»

Eis um rigoroso artigo sobre o tema:

«Au fait, qu'est-ce qu'un contre-ténor ? Peu de dénominations ont suscité autant de querelles d'experts ! Tout, d'ailleurs, a commencé par un malentendu. En 1943, le compositeur Michael Tippett entend à Canterbury un chanteur à la voix angélique, qui semble n'avoir pas mué : Alfred Deller. Il croit avoir retrouvé la trace de ce mystérieux «contre-ténor» qu'évoquaient Purcell et Bach. Deller, pourtant, ne revendique nullement ce titre : il se qualifie d'alto ! Autrement dit, la voix féminine grave. D'où vient la méprise ?

Klaus Nomi un contre-ténor à l'heure du rock

À l'époque baroque, le terme « contre-ténor » ne désigne pas une technique de chant, mais une ligne sur une partition : celle qui est au-dessus de la partie de ténor. Le terme le plus juste pour qualifier le type de voix ressuscité par Deller serait celui de «falsettiste», car il a recours à la voix de fausset, la «voix de tête». À ne pas confondre avec la «haute-contre», ténor aigu chantant en voix de poitrine ! Les falsettistes (ceux que nous appelons aujourd'hui «contre-ténors», vous suivez toujours ?) ont fleuri au début de l'époque baroque, mais ils ont progressivement disparu, remplacés au XVIIIe par les tout puissants castrats, et au XIXe par les ténors à la voix virile et puissante. Finie, la nostalgie du troisième sexe, fascination pour un corps d'homme produisant des sons de femme.

David Daniels. Bouleversant dans Theodora de Haendel.

Deller fut le premier à redécouvrir cette manière de chanter. Sa voix pure était délicate, plus appropriée aux chants religieux qu'à l'opéra. Mais dès les années 1950, l'Américain Russell Oberlin, montra que l'on pouvait être contre-ténor et acteur. Sa fragilité vocale (épine dans le pied des contre-ténors) ne résista pas à l'opéra, jusqu'à ce que l'Anglais James Bowman vienne montrer que le falsettiste pouvait avoir une voix puissante. La lame de fond de la musique baroque, dans les années 1970, fit éclore des générations de contre-ténors influencés par René Jacobs et son chant complet : voix de poitrine incarnée dans le grave, voix de tête éthérée dans l'aigu. Henri Ledroit, Gérard Lesne, plus tard Andreas Scholl suivirent cet exemple, tandis que l'extraterrestre Klaus Nomi mettait le contre-ténor à l'heure du rock.

Côté américain s'imposait une image virtuose et théâtrale du contre-ténor, loin de tous les clichés : David Daniels, Lawrence Zazzo, Bejun Mehta, sont ces bêtes de théâtre qui affrontent les personnages de guerriers des opéras de Haendel. Du moins quand on les leur confie : car leur ex-collègue Jacobs, devenu chef, s'est mis à soutenir qu'une mezzo soprano était plus appropriée ! D'ailleurs, quand Haendel ne disposait pas d'un castrat, ne recourait-il pas à une femme ? En revanche, le répertoire s'étend, car les compositeurs de notre temps se sont vite intéressés à cette voix : de Britten, avec Le Songe d'une nuit d'été, à Peter Eötvös, dont l'opéra Trois Sœurs est écrit pour trois contre-ténors.»

Met opening night II : Tosca (September 2009)

(da esquerda para a direita - George Gagnidze, como Scarpia, Marcello Álvarez, como Mario Cavaradossi, e Karita Mattila, como Floria Tosca)

Até à data, apenas li críticas de jornais europeus à Tosca de Bondy, advirto.

Objectivamente, houve um rotundo e sonoro apupo na noite de estreia. Não é que isso seja sinónimo de algo relevante - uma das mais extraordinárias produções a que assisti (Peter Grimes, Bastilha - 2001) foi esmagada por uma interminável pateada.

Voltando à première desta nova produção, tudo leva a crer que o conservadorismo estético do público não tolerou a ousadia de Bondy. É bem verdade que o público da Met Opera House acarinha em demasia as propostas de Zeffirelli. Pessoalmente, abomino-o: é de uma megalomania insuportável e de um hiper-realismo entediante. Incapaz de abandonar os velhos clichés, o encenador italiano limita-se a ampliar as indicações dos libretos...

Bondy é de outro calibre! A sua Salome é um assombro: impregnada de decadência e luxúria... O Don Carlos do Châtelet é um dos maiores mitos da mise-en-scène, de uma beleza e riqueza simbólica absolutamente invulgares!

Por ora, eis o veredicto do Le Monde:

«Tosca (1900), de Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924), mis en scène par Luc Bondy, présenté, lundi 21 septembre, en soirée de gala devant un parterre huppé (où les zibelines, les robes haute couture et les nez refaits abondaient), a pris un bouillon terrible, une huée vengeresse criée du fond du ventre par un public furieux qu'on lui ait enlevé "sa" Tosca. Celle qu'il voyait depuis 1985 sur la scène du Met, concoctée par l'Italien Franco Zeffirelli. Car le public du Met, du moins sa majorité tonitruante, veut une Tosca en CinémaScope, avec son église baroque au premier acte, son palais Farnèse au deuxième et, au troisième, son château Saint-Ange, avec vue imprenable sur Saint-Pierre et le Vatican.

(...)

Pourtant, ce spectacle est l'une des (rares) incarnations de ce que peut être une soirée d'opéra parfaite : une direction d'acteurs fine, qui n'impose rien aux chanteurs mais organise leur liberté différemment ; un décor d'une beauté austère mais soufflante, dont la monumentalité n'empêche pas les qualités de réverbération acoustique ; un chef, James Levine, qui ne confond pas expérience et routine (il a dirigé sa première Tosca au Met en 1971), calme et ennui, volupté et débauche ; un orchestre dont on ne connaît pas, dans le monde, d'équivalent en précision et en subtilité ; et une distribution de rêve : une Tosca atypique mais jeune, ardente, incarnée par une Karita Mattila qui parvient même à faire de ses limites vocales (dans l'aigu) des qualités dramatiques, un ténor, Marcelo Alvarez, qui est peut-être ce qu'on peut entendre de plus beau aujourd'hui dans ce genre d'emploi (il sera André Chénier à l'Opéra de Paris, en décembre), et un baryton, George Gagnidze, Scarpia noir et glaçant, encore inconnu mais qui promet d'être un immense chanteur.»

Ou muito me engano ou espera-me uma FABULOSA TOSCA!

ps a crítica é de Renaud Machart, cuja snobeira há dias caracterizei...

domingo, 20 de setembro de 2009

Vil Metal & Escolhas

Aguardo ansiosamente pela rentrée discográfica (da lírica, particularmente). Desde que me vi privado de assistir a ópera de qualidade na capital portuguesa, a minha voracidade por registos discográficos cresceu a olhos vistos - já era o que era, agora então...

Posto que o vil metal não é inesgotável, optei por circunscrever os registos que irei adquirir. O mesmo é dizer que recorri à banda gástrica.

Eis, pois, os meus imprescindíveis da rentrée (que facilmente ascenderão a cerca de €200):

Posto que o vil metal não é inesgotável, optei por circunscrever os registos que irei adquirir. O mesmo é dizer que recorri à banda gástrica.

Eis, pois, os meus imprescindíveis da rentrée (que facilmente ascenderão a cerca de €200):

Disse-me um passarinho...

...que há mais novidades suculentas (desta feita, mais demoradas) na forja!

sábado, 19 de setembro de 2009

Mireille - Opéra National de Paris

«(...) l'Opéra de Paris présentait, le 14 septembre, Mireille (1864), de Charles Gounod (1818-1893), dans une mise en scène de Nicolas Joel, le nouveau directeur de l'établissement, qui fleure bon les senteurs sépia de l'"opéra-à-papa".

On ne sache pas que Nicolas Joel, qui a succédé au turbulent Gerard Mortier, soit un génie visionnaire de la mise en scène lyrique, mais on n'imaginait pas que ce professionnel reconnu puisse présenter un travail aussi dénué de sens dramatique et de direction d'acteurs. Il suit à la lettre le livret adapté de Mirèio (1859), le poème épique en occitan de Frédéric Mistral, qui narre le destin tragique d'une jeune Provençale de bonne famille rurale, amoureuse non d'Ourrias, auquel son père l'a promise, mais de Vincent, le fils d'un simple fermier. Tout se passe, ainsi que prescrit, en Provence, entre le désert de la Crau, le val d'Enfer et les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer.

Mais fallait-il pour autant ce décor (signé Ezio Frigerio) au réalisme ringard et maladroit, ces danses grotesques, ces fleurs artificielles qui garnissent les arceaux d'une carriole et un Rhône sous la lune digne d'une carte postale en relief ? Cette dernière scène a même fait ricaner certains et déclenché les premières huées.

On s'est pincé en voyant les chanteurs revenir aux bonnes vieilles postures d'antan : main sur le coeur, bras au ciel, genou à terre. Un vétéran tel qu'Alain Vernhes (qui joue le père de Mireille) ou un talent aussi naturel que l'excellent Franck Ferrari (Ourrias) se débrouillent seuls, pour ainsi dire.

Mais ce n'était pas le cas d'Inva Mula, appréciée de longue date par Nicolas Joel. La soprano albanaise joue et chante Mireille dans un registre suranné et totalement artificiel qui la fait prendre, avec sa natte blonde, alternativement pour Heidi et pour une gamine de la série télévisée "La Petite Maison dans la prairie". Ses minauderies ravissent à Gounod la simplicité géniale de son invention (l'air Heureux petit berger en devenait ridicule) et ruinent les grandes scènes de la fin de l'ouvrage. La soprano n'est pas indigne dans ce lourd rôle, mais savonne les vocalises, ne nourrit jamais ses aigus pianissimos (émis en voix de tête), et a une diction généralement incompréhensible.

En revanche, on découvrait la voix, un peu fermée et de calibre modeste, mais chaude et si émouvante, de Charles Castronovo (Vincent). Le jeune ténor américain est un fin musicien, et prononce un français quasiment parfait. Très marquante Taven, de Sylvie Brunet, qu'on a plaisir à réentendre sur la scène de l'Opéra de Paris, et intervention idéale de Sébastien Droy, dans l'air du pâtre, peut-être le plus touchant de Mireille.

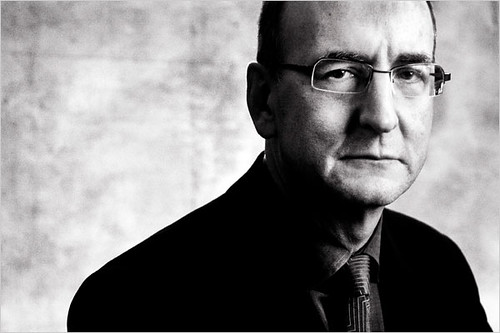

Avec une Mireille de chair et de sang, la partie musicale de la soirée aurait pu être parfaite, car Marc Minkowski l'a dirigée avec soin, amour et gourmandise. Le chef, venu du milieu de la musique baroque, sait entendre et révéler les archaïsmes et le classicisme de la partition, mais aussi faire sonner merveilleusement une "musette" délicate ou, au début de l'acte V, un carillon comme entonné par une banda bruyante. On ne l'a pas toujours épargné en ces colonnes, mais, ce 14 septembre, il ne méritait pas les quelques huées qui lui ont aussi été adressées.»

A Opéra National de Paris abriu a temporada lírica 2009 / 2010 a 14 de Setembro, com uma obra raramente interpretada, Mireille, de Gounod.

É certo e sabido que Gounod não me fascina. Aliás, por regra – apesar da minha costela francófona –, a opera francesa não me preenche. Ainda assim, arrisco duvidar da critica que acima transcrevi do Le Monde.

O estilo de Renaud Machart, poeirento, repetitivo, snob e decadente – sempre apoiado no desprezo e desdém – fez escola em Portugal, sendo Jorge Calado o seu mais proeminente representante.

Se mandarmos o crítico bardamerda e apanharmos o avião para Paris, hoje ainda (data da segunda récita), ficaremos muito mais felizes e poderemos avaliar com os nossos próprios olhos – de vis terrenos e por demais incultos, é certo... – a qualidade desta Mireille!

Don Carlo - Royal Opera House Covent Garden

(Don Carlo - Royal Opera House, Setembro de 2009)

«That great scene was wonderfully played by Simon Keenlyside (Rodrigo) and Ferruccio Furlanetto (Philip II). Furlanetto is that special breed of singing actor for whom gravitas is inbred. We see a broken man disintegrate before our eyes in his great act four aria; we feel his anger and defiance in the encounter with John Tomlinson's craggy Grand Inquisitor who manages to turn the word "Sire" into a condescending growl. These are credible portrayals. Less so Marianne Cornetti's indomitable Eboli; hers is a voice of considerable fire power, but she's hopelessly woolly in the lacy coloratura of her folksy Veil aria.

One of the most effective devices in Hytner's staging – and I still find the garish pop-up aspects of Bob Crowley's design alienating – is Carlo's isolation, the descending front cloth of ancestral tombs a constant reminder of his grandfather's weighty legacy. Jonas Kaufmann carried this romantic idealism magnificently, thrilling in his full-throated anguish, tender in his love for Elizabeth de Valois with mezza voce phrases literally melting in the singing of them.

Marina Poplavskaya (Elizabeth), beautiful and intense on stage, is not a natural Verdian, the voice too white and unyielding, the lack of through-phrasing conspicuously unidiomatic. But in the perfect symmetry of their first and last encounters there was a real frisson between she and Kaufmann. The numbing pianissimo of their final moments together carried such regret and resignation as to unlock the very heart of a great piece.»

«New to the cast are Jonas Kaufmann's Carlo, Marianne Cornetti's Eboli and John Tomlinson's Inquisitor. Cornetti, hogging the high notes and doing nothing with the character, is the evening's main vocal drawback. Tomlinson, on the other hand, scares you half to death with every utterance. And Kaufmann is outstanding, whether braving the rages of Ferruccio Furlanetto's tragic Philip, swooning over Marina Poplavskaya's Elisabetta, or getting political with Simon Keenlyside's finely acted, if undersung Posa.»

Ainda por terras londrinas, no caso deste Don Carlo - contrariamente a Le Grand Macabre -, o elenco é a vedeta. Quando Carlo é Jonas Kaufmann, Rodrigo é interpretado por Keenlyside e Furlanetto veste a pele de Filippo II, tudo o resto é (quase) irrelevante...

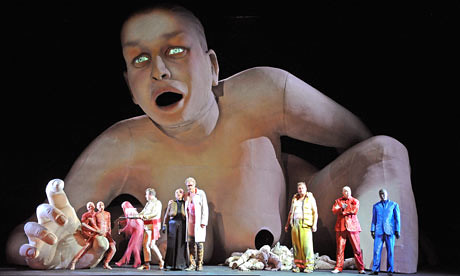

Le Grand Macabre - English National Opera

(Le Grand Macabre - ENO, encenação de La Fura Dels Baus)

«But now London has a chance to sample another strand of La Fura's oeuvre, when English National Opera presents its production of György Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre, first seen in Brussels earlier this year. It sold out and won rave reviews: after seeing it, wrote one critic, "even the terminally depressed would be ready to dump the Prozac and pull the chain". Ligeti described Le Grand Macabre as an "anti anti-opera". An exuberant jet-black farce, loosely based on a play by the Belgian surrealist Michel de Ghelderode, it was first performed in 1978, at a time when Boulez and other puritans had made "anti-opera" a fashionable concept. Ligeti, a member of the same avant-garde but a rebel against all orthodoxies and trends, was having none of it: he decided instead to write the most brazenly operatic opera he could, parodying all its conventions and following an extreme story-line, filled with fantasy characters, bawdy jokes and flamboyant gestures.

Yet its underlying theme is deadly serious, quite literally so. It asks, why are we so afraid of death? In Breughel-land, those in charge are obese and corrupt, and about to be popped off by revolutionaries. The charlatan Nekrotzar, "le grand macabre", claims to have returned from the grave to devastate the earth, while the transvestite astrologer Astradamors prophesies that a comet spells further doom. Everyone else is drunk, sex-obsessed or plain moronic. But somehow, the death and destruction that terrifies everybody into their bad behaviour never materialises: the only truth is that life is a lottery, so it's better to be fatalistic and enjoy yourself.

Le Grand Macabre is a classic of late modernism, yet there's been no major production for over a decade.

For La Fura dels Baus, it's a natural fit and audiences at ENO can expect to be shocked and entertained in spades, as Alex Ollé and Valentina Carrosco have focused their staging on a giant revolving fibreglass figure of a naked woman, modelled on their friend Claudia. The action takes place in and out of Claudia's orifices, with costumes linked to bodily organs. Video of the real Claudia is projected on to the surface of the figure, showing her apparently worrying herself to death as she gorges on junk food ("le Grand Mac") and reads petrifying headlines in the newspapers.

Technically, the remotely controlled model of Claudia is a tour de force. "We've done 14 performances and so far nothing's gone wrong," Carrosco says, touching wood. Ollé insists it's not a gimmick, but a rich metaphor for Ligeti's theme, and the sense that fear of death is something that we feel in our bones.

"We don't want empty spectacle," Ollé says. "The work that we've done with the singers is the heart of the production and we've been lucky to find performers who are so receptive to a complete theatrical experience."»

O leitor atento sabe das minhas reservas face aos vanguardistas (?) La Fura dels Baus...

«So begins this extraordinary staging – by Alex Ollé and Valentina Carrasco of the Catalan “total theatre” company La Fura dels Baus – of György Ligeti’s only opera. Claudia is designer Alfons Flores’ creation and she fills the Coliseum stage revolving through 360 degrees to reveal every unflattering aspect of her physiognomy. They say no man is an island, but this woman is. Or to be more precise, she is Breughelland, a paranoid and morally corrupt police state run by a sexually indeterminate Prince sporting a very high voice and lurex tunic (the excellent Andrew Watts). And when a mysterious visitor Nekrotzar (Pavlo Hunka) arrives to announce that the game will be up at precisely midnight, Claudia’s body becomes a repository for the entire world’s fear and loathing.

Allé and Carrasco’s production literally spills from her every orifice. At one point the black and white ministers (or should that be minstrels) of Breughelland (Daniel Norman and Simon Butteriss) emerge, appropriately enough, from her rear end to engage in a slanging match of A-Z obscenities. Claudia’s bowels (groaning under the weight of all that bingeing) are massaged by black-gloved hands before the Chief of Secret Police, Gepopo (the manic coloratura soprano of Susanna Andersson) explodes from within smelling subversion and foul play. Or is that simply smelling foul. Claudia’s worst nightmare, and ours, is an Hieronymous Bosch-like landscape of degradation and delight on which startling video projections (Franc Aleu) cast images of hellfire and decay. Claudia’s fleshly form dissolves into a skeleton before our eyes. Amazing.»

A obra de Ligeti, Le Grand Macabre - não suscitando reserva alguma da minha parte -, mantém-se envolta em polémica, irreverência, ousadia e provocação.

No meio de tudo isto - reservas & polémicas - , é difícil esconder o desejo e curiosidade pela proposta dos catalães...

«This production is all about the set, a gigantic revolving figure of a naked women on all fours, whose orifices and detachable nipples and limbs provide endless scope for exits and entrances. Combined with a dazzling use of video, the visuals are spectacular, but they hardly seem specific to Grand Macabre»

Verdadeiramente, só os burros não mudam.

Ecos verdianos de Álvarez

«The Argentinian tenor Marcelo Álvarez has been tipped as the successor to Pavarotti as the pre-eminent Verdi interpreter of his era, and as these Verdi arias demonstrate, he lacks none of the technical prowess that requires.,/p>

Indeed, there are distinct echoes of Pavarotti in Álvarez's "Oh! fede negar potessi", though he delivers with passion rather than power, before offering an empathic "Quando le sere al placido". Elsewhere, he negotiates the emotion of Manrico's deathly promise "Ah! si, ben mio" from Il Trovatore in measured manner, before wringing every last ounce of emotion out of the hero's death scene from Otello.»

Álvarez sucessor de Pavarotti??? Pavarotti: intérprete verdiano de referência???

Bom... há coisas que não se discutem, dada a patetice de que enfermam.

Álvarez é um grande, grande tenor - cujo Duque (Rigoletto) me impressionou muitíssimo, há uns bons dez anos, na Bastilha. Consta que brilha ainda como bel cantista - Edgardo, entre outros. Isto são factos.

Na ausência do objecto, tive de me contentar com a opinião - tão sucinta, quanto polémica - do The Independent.

Logo que o registo me chegue à mão, outro galo cantará!

domingo, 13 de setembro de 2009

Metropolitan Opera House - 2009/2010

Eis a síntese das premières a que o público do Met poderá assistir na temporada que se avizinha:

«PATRICE CHÉREAU has been a prominent director in Europe since his 1976 staging of the “Ring” cycle at the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth, Germany, which placed him at the forefront of Regietheater, a term applied to high-concept, sometimes outlandish reinterpretations of operas.

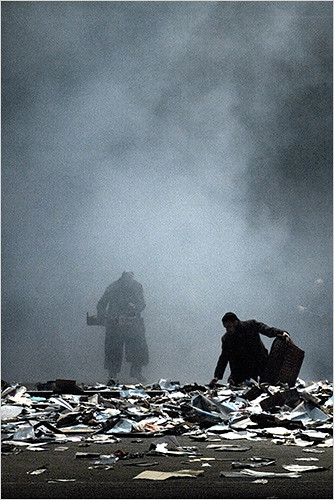

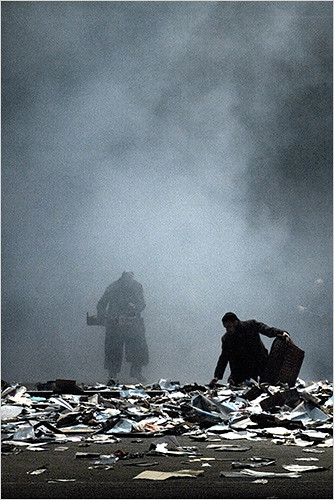

Peter Gelb, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera since 2006, will presumably not import some of the tackier elements of Regietheater. But he has recruited major directors from theater and film for recent stagings, with varying degrees of success. As part of the first season planned entirely by Mr. Gelb and the music director, James Levine, Mr. Chéreau will make his American debut with Janacek’s dark “From the House of the Dead.”

One of eight new stagings at the Met this season, “From the House of the Dead,” a co-production with several European companies, will open on Nov. 12 with Esa-Pekka Salonen in his house debut, conducting a cast that includes the excellent baritone Peter Mattei.

The opera is Janacek’s last and is based on Dostoevsky’s novel “The House of the Dead,” a fictional account of life in a Siberian prison camp inspired by his own experiences. Written for a large and almost entirely male cast and chorus, the Janacek opera had its premiere in Brno, now in the Czech Republic, in 1930, two years after Janacek’s death. It is seldom staged.

Janacek wrote his own libretto and specified that the action should take place in the Siberian countryside. Mr. Chéreau’s widely praised production uses enormous gray walls to suggest a modern prison. Within those walls, Mr. Chéreau suggests, exist the same power struggles, relationships, humiliations and passions of contemporary society.

On a more lighthearted note, the imaginative South African artist William Kentridge, who designed the sets for a production of Mozart’s “Magic Flute” seen at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2007, will also make his Met debut with a new production of “The Nose,” by Shostakovich, opening on March 5.

The Met recruited visual artists like Marc Chagall and David Hockney to design sets. Mr. Kentridge’s production will incorporate archival footage and animated films as well as plaster and papier-mâché costumes for the title character.

Valery Gergiev will conduct Shostakovich’s theatrical score, a blend of folk music and atonality that had its premiere in Leningrad in 1930. Paulo Szot, now starring in “South Pacific” on Broadway, will play Kovalyov, the bureaucrat drawn from Gogol’s 1836 satire about a civil servant who wakes up and discovers he has lost his nose. When Kovalyov confronts the missing appendage, he learns that it has attained a higher rank than his own. But man and nose are reunited in a happy ending.»

(fotos de O Nariz - à esquerda - e Da Casa dos Mortos - à direita)

«PATRICE CHÉREAU has been a prominent director in Europe since his 1976 staging of the “Ring” cycle at the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth, Germany, which placed him at the forefront of Regietheater, a term applied to high-concept, sometimes outlandish reinterpretations of operas.

Peter Gelb, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera since 2006, will presumably not import some of the tackier elements of Regietheater. But he has recruited major directors from theater and film for recent stagings, with varying degrees of success. As part of the first season planned entirely by Mr. Gelb and the music director, James Levine, Mr. Chéreau will make his American debut with Janacek’s dark “From the House of the Dead.”

One of eight new stagings at the Met this season, “From the House of the Dead,” a co-production with several European companies, will open on Nov. 12 with Esa-Pekka Salonen in his house debut, conducting a cast that includes the excellent baritone Peter Mattei.

The opera is Janacek’s last and is based on Dostoevsky’s novel “The House of the Dead,” a fictional account of life in a Siberian prison camp inspired by his own experiences. Written for a large and almost entirely male cast and chorus, the Janacek opera had its premiere in Brno, now in the Czech Republic, in 1930, two years after Janacek’s death. It is seldom staged.

Janacek wrote his own libretto and specified that the action should take place in the Siberian countryside. Mr. Chéreau’s widely praised production uses enormous gray walls to suggest a modern prison. Within those walls, Mr. Chéreau suggests, exist the same power struggles, relationships, humiliations and passions of contemporary society.

On a more lighthearted note, the imaginative South African artist William Kentridge, who designed the sets for a production of Mozart’s “Magic Flute” seen at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2007, will also make his Met debut with a new production of “The Nose,” by Shostakovich, opening on March 5.

The Met recruited visual artists like Marc Chagall and David Hockney to design sets. Mr. Kentridge’s production will incorporate archival footage and animated films as well as plaster and papier-mâché costumes for the title character.

Valery Gergiev will conduct Shostakovich’s theatrical score, a blend of folk music and atonality that had its premiere in Leningrad in 1930. Paulo Szot, now starring in “South Pacific” on Broadway, will play Kovalyov, the bureaucrat drawn from Gogol’s 1836 satire about a civil servant who wakes up and discovers he has lost his nose. When Kovalyov confronts the missing appendage, he learns that it has attained a higher rank than his own. But man and nose are reunited in a happy ending.»

(fotos de O Nariz - à esquerda - e Da Casa dos Mortos - à direita)

sábado, 12 de setembro de 2009

Sacrificium

Sexta-feira, dia 18 de Setembro, entre as 12.00 e as 13.00 (hora de Lisboa), Cecilia Bartoli pode ser interpelada pelos leitores do El Pais, on-line, no âmbito da promoção do seu próximo registo, Sacrificium. Aproveitem!

«Durante unos 300 años, cientos de niños fueron castrados en Italia en nombre de la música. La prohibición de cantar a las mujeres impuesta por la Iglesia hizo que florecieran los 'castrati'. Ahora, la conocida mezzosoprano Cecilia Bartoli se adentra en este mundo con un nuevo disco, Sacrificium, en el que recoge las arias más expresivas escritas para los castrati más populares, como Farinelli, Caffarelli... La italiana charlará con los lectores sobre este nuevo trabajo y su carrera musical.»

Para os mais ansiosos, aqui fica a possibilidade de apalpar o terreno de Sacrificium, com gosto! Basta registar-se e fruir...

«Durante unos 300 años, cientos de niños fueron castrados en Italia en nombre de la música. La prohibición de cantar a las mujeres impuesta por la Iglesia hizo que florecieran los 'castrati'. Ahora, la conocida mezzosoprano Cecilia Bartoli se adentra en este mundo con un nuevo disco, Sacrificium, en el que recoge las arias más expresivas escritas para los castrati más populares, como Farinelli, Caffarelli... La italiana charlará con los lectores sobre este nuevo trabajo y su carrera musical.»

Para os mais ansiosos, aqui fica a possibilidade de apalpar o terreno de Sacrificium, com gosto! Basta registar-se e fruir...

sexta-feira, 11 de setembro de 2009

quinta-feira, 10 de setembro de 2009

Floria Tosca & Dissoluto

Our long time love affair...

See you soon - once more -, Dear Karita ;-)

nota: a lascívia oculta virtudes maiores. Sei muito bem do que falo!

domingo, 6 de setembro de 2009

N'Importe Quoi!! (II) - Twitterdammerung

A famigerada Twitter Opera (Twitterdammerung) - cujo libreto foi composto a partir de mensagens enviadas por cerca de 900 utilizadores do twitter - lá estreou no Covent Garden. Nem bem, nem mal; nem sim, nem sopas...

Segundo reza a crónica, há coisas piores, havendo melhores, também. Elucidativo!

«But the jumper proved of no value, as what unfolded before me was actually not that bad at all. I mean actually watchable, listenable and rather funny. Don't get me wrong; madness and messiness, in the main, did dictate the tone.

Reitero o que disse a propósito da iniciativa: N'Importe Quoi!

Se, verdadeiramente, a ideia subjacente à iniciativa é captar novos públicos para a lírica - como sugere o crítico -, ofereça-se boa ópera, bem interpretada e cantada!

Vão ver se não vinga!